|

Preliminary Comments This article is more academic than most of the other fare on this blog. It previously appeared in 2005 in the Journal of Conscientiology, Vol.7 No.27:203-221, and it follows formatting conventions I used there. I have decided to reproduce it here to make it more widely accessible for a few reasons. One is that I regularly encounter questions about rainmaking and this usefully sums up my understanding on the matter. The other is that humanity's impact on the weather is becoming an ever more urgent issue. Addressing physical pollution is clearly a priority in this regard, but the importance of addressing our mental pollution cannot be underestimated. Our relationship with nature begins in our thoughts and emotions, and real life actions flow from them. The idea that we can control the weather with our energies, which are directed by our mind and intention, introduces a degree of consciousness and deliberateness that is largely lacking in our present society when it comes to the weather and climate. Despite all the ways western "civilisation" has domesticated nature, we feel as if we are at the mercy of the weather, while those in denial of climate change claim that our actions have no consequence. This is in stark contrast with indigenous approaches, where it is absolutely assumed that human actions have repercussions on the world around us and that humans can control the environment through conscious actions. As this article documents, those beliefs have been mocked by Europeans ever since colonisation began and there are plenty of people who still mock them. As I argue in this paper, although advanced in the name of science, such dogmatic ridicule is actually a completely anti-scientific approach. I would suggest that this is the point in history where we need to examine indigenous approaches again with fresh eyes and consider whether we can learn anything from them for the way we relate to and engage with the environment. Introduction Reality. In the 1940s, the Italian anthropologist Ernesto De Martino (1997) used the ethnographic literature to show that the “impossibility” of certain phenomena, such as telepathy and precognition, arises from preconceptions, not facts. Rainmaking is a case in point. Your underlying view of reality will determine whether you consider it possible for human consciousness to cause rain. Science. For mainstream scientific discourse, the idea that humans could make rain by force of will and, for example, singing and dancing is absurd. For most indigenous societies it is a given (cf. Berndt & Berndt, 1964, p.252). Record. Rainmaking ceremonies have been recorded across Aboriginal Australia (McCarthy, 1953). The quality and format of their descriptions varies widely. In many cases, recorders did not actually observe the ceremony, but were told how it should be done and what should happen. On other occasions, they attended the ceremony, but do not mention the outcome. Open Mind. Almost all reporters make some comments, which indicate that they did not approach the subject with an open mind, like the following:

Success. The evidence I have considered shows that not all rainmaking ceremonies are successful, but many accounts by anthropologists and other observers do speak of rain falling shortly after a ceremony (Berndt, 1947, p.365; Berndt & Berndt, 1944, p.133; Duerr, 1985, pp. 287- 288; Goddard, 1932; Hercus, 1977, pp. 69-71; Horne & Aiston, 1924, p.120; Reid, 1930; Strehlow, 1971, pp.434-436; White, 1979, p.99). Choice. Even when it rains, however, we have no choice but to adopt explanations of “coincidence” or “deceit” as long as we believe it impossible for human consciousness to act upon the weather. Analysis. The premises of the consciential paradigm enable us to accept the possibility that consciousness can affect the weather and consequently allow a functional analysis of Aboriginal ceremonies. Relevance. The relevance of such analysis goes beyond the explanation of a specific practice. Rainmaking is only one of numerous practices that arise within societies that prioritise multidimensionality. Such societies seek to manipulate the physical dimension through the power of consciousness in many areas of life; they are fundamentally multidimensional societies. Anthropological explanations Parrots. It is an accepted scientific principle to draw on research and conclusions of others. That can be reasonable, as there is no point in continuously reinventing the wheel. It becomes a problem when it leads to the parroting of badly obtained research results or prejudiced opinions. Heresy. The fact that a statement increases in authority with each repetition is observed in both popular (media) and scientific discourse. Repeating statements can lead to creating and re-affirming a consensus reality until stating a contrary view becomes an act of heresy that provokes ridicule or abuse. This is very relevant to the multidimensional study of consciousness, because such study is based on premises that have long, repeatedly and vehemently been declared impossible by the dominant scientific discourses. Working with those principles thus becomes an heretic act in the eyes of the wider scientific community. Anthropologists. Most anthropological studies of rainmaking suffer that crippling effect. With very few exceptions, they consider rainmaking an impossibility and because of that premise they do not spend any time looking at how it may work. Their premise itself is never questioned, because that would be heretical. Explanations. As a result, anthropologists have either not tried to explain successful rain making at all or they have chosen one of two explanations: 1. Perception. 2. Chance. Perception. The “perception” explanation is that the rainmaker is a particularly perceptive person who is aware of minute environmental changes which show him or her that rain is likely to fall in the near future. According to this argument, rain is only “made” when the signs of nature, perceived exclusively by the rain-maker, show that it is imminent. Culture. Researchers have commented on the remarkable, culturally encouraged, perceptiveness of Aboriginal people (e.g. Poirier, 1996, pp.189-190). There is no doubt that Aboriginal people who have grown up in the bush are more capable of foretelling future weather by environmental signs than most white people would be. Heightened perception and knowledge of nature is a general characteristic of traditional Aboriginal people. It is precisely for that reason that the perceptiveness argument is flawed. Signs. Both women and men, young and old are capable of seeing signs in nature, for example those that indicate the availability of natural resources (Rose, 1997). It is fair to assume that many traditional Aboriginal people will be able to notice signs of pending rain, not just the specialised rainmakers. Special. Consequently, it would not make sense for rainmakers to be accorded special status for making something everybody knew was coming anyway. Community. In societies where rainmaking ceremonies are complex communal processes, this argument lacks further logic. For example, in Howitt’s description of rainmaking among the Dieri (Howitt, 1996, pp.394-396) first the “great council” determines that it is time for such a ceremony, because of long lasting drought. Messengers are then sent out to the scattered camps to gather everybody together for a communal ceremony. Other authors also describe careful consultation (Berndt, 1947, p.361; Rose, 1997, p.4) and extensive ceremonies involving hundreds of people (Tonkinson, 1972; White, 1979). Clearly people are going to this extent because they believe it is effective, not because they know that it is about to rain anyway. Trickster. Some try to overcome this by suggesting that the deviant, yet perceptive, rainmaker is tricking the wider community. This idea implies a naivety that is not supported by the facts. The earlier argument about culturally practiced perceptiveness is relevant again. In addition, there are many Dreaming stories involving a trickster, who in one way or another fools another individual, or the entire community. This invites the proposition that people are quite aware of the possibility of being conned and would be capable to keep an eye out for it. Chance. Mainly amateur reporters use another argument, even less satisfying than perception. Comfortable in their “scientific” knowledge that one could never make rain by chanting and dancing, they simply dismiss any successful occasion they may observe as a stroke of luck. Exception. The following view of the anthropologist Long is still an exception: In spite of many observations of such phenomena by anti-psi anthropologists, even they cannot find failures in rainmaking to equal the successes. Hence, contrary to what is known about atmospheric causation, one is inclined to accept that rainmaking (and stopping) is successfully practiced and has a very high survival value. (Long, 1977, p.384) The Social context of rainmaking Terminology. Anthropology classifies rain making together with other ritual activities as imitative or sympathetic magic (Frazer, 1996; Tonkinson, 1972, p.67). These terms refer to ritual actions that in some form imitate or incorporate the characteristics of that which they seek to influence. Outcome. Sympathetic magic can be divided into two different forms according to the desired outcome. Increase or maintenance ceremonies are usually social activities concerning the well-being and economic obligations of the wider group. Witchcraft or sorcery is usually an anti-social activity aiming at the well being of one particular person to the detriment of other people. Responsibility. In Aboriginal Australia, different groups of intraphysical consciousnesses within a given society are responsible for different species in the natural environment. Usually this responsibility will arise from the totem of the intraphysical consciousness. Totems. In many societies, a totem is obtained by birth or conception at a particular place, or by inheritance. Totems are usually a species of flora or fauna; more importantly they relate to one or more Dreaming ancestors, i.e. extraphysical consciousness. Inter-dependence. Traditionally, individuals and their totem were inter-dependent: humans might have physical or psychological features relating to those of their totem (paragenetics) and special obligations for their totem. Increase ceremonies. For example, humans of the kangaroo totem will be charged with ensuring a sufficient supply of kangaroos by regularly attending to the kangaroo increase ceremonies. In most societies, people with the primary responsibility for rainmaking would have rain as their totem, or one of the ancestral beings associated with making rain, often a serpent referred to in English as the “rainbow serpent” (Poirier, 1997; Tonkinson, 1972). Censure. Should a certain species be scarce one year, others may censure those of that totem for failing in their duties. Rainmakers may be censured for the absence of rain, but also if there is a surplus leading to destructive floods (Trezise, 1985). Witchcraft. Detailed ethnographic accounts of Aboriginal Australia are replete with references to sorcery, usually malign and with the aim of killing or mentally disturbing another intraphysical consciousness. Most of these practices are secretive and involve one individual or a group focusing intensely negative energies at another individual, who is “sung” or “pointed” (e.g. Elkin, 1994, p.40; Howitt, 1996, pp.359-378; Peile, 1997, pp.137-139; Warner, 1937, pp.194-210). Revenge. People could make or withhold rain, and produce storms or lightening in revenge to kill or harm others (e.g. Hercus & Koch, 1996; Tonkinson, 1972, pp.115-116). While it could be used for negative, individualistic purposes, more commonly it was a beneficial activity, only done at socially recognised times and by the appropriate people. Networks. Even where rainmaking ceremonies were not communal events, but confined to a few specialised rainmakers, these did not operate in a social vacuum. They were part of regional networks and their abilities and role were recognised far beyond their immediate group. Rainmaking was not a frivolous activity. Influencing the weather Psychokinesis. Parapsychologists have satisfied themselves that human consciousness can produce small effects on intraphysical events (psychokinesis). Most experiments have focused on the ability of the human consciousness to influence random number generators or dice. Reviewing the available data on these experiments, Radin (1997, p.144) concludes that there is evidence that consciousness can act upon physical systems through the force of will. Systems. Weather is a substantially larger system than a number generator or dice. It is influenced by a complex interplay of evaporation, forests, geography (geo-energies), lunar energies, pollution, solar energies, volcanic activity, winds and many other factors. Extraphysical consciousness. Crucial to this discussion is the hypothesis that, as well as many physical variables, extraphysical consciousnesses play a role in regulating the weather on this planet. Climate. The weather is not the same as the climate. The climate of an area is determined by the composite of its weather over a prolonged period. A day’s weather is a building block for the macro-system of climate. The climate is a much greater system to change than the weather. Wishing. Radin cites a study by Nelson that compared the weather at Princeton University on graduation days with those of six surrounding towns. The theory was that the thousands of people coming to Princeton that day would be wishing for good weather. The study “revealed that on average, over thirty years, there was indeed less rain around graduation days than a few days before and after graduation, with odds of nearly twenty to one against chance. An identical analysis for the average rainfall in six surrounding towns showed no such effect.” (Radin, 1997, p.172; cf. Nelson, 1997) Sunday. A less detailed study, based on the same assumption, in this case that people would wish for good weather on Sundays, found a similar suggestion. “According to newspaper records, there were 211 days when the sun did not appear by afternoon press-time at St Petersburg, Florida, from 1910 through 1957. Only eleven of these days were Sundays.” (Cox, 1962, pp.172-173). Field-consciousness. Radin uses the term field-consciousness to describe the effect of larger numbers of intraphysical consciousnesses focusing on the same event. Conscientiology would speak of a group-holothosene. The field-consciousness Radin describes is often produced unconsciously, as in the many individuals wishing for good weather. Discipline. Aboriginal rainmakers are mentally and energetically well-trained. Meditative and projective techniques were part of their culture as were other forms of mental discipline. Intention. It is the hypothesis of this author that consciously focused intent of only a few such individuals is more likely to influence the weather than the idle wishes of a larger population desiring a sunny Sunday. The structural elements of the ceremonies Essentials. In spite of the great variety of rainmaking ceremonies across Australia (McCarthy, 1953), there are recurring essential elements. They may not all occur in every ceremony, but they stand out in the literature surveyed. Those elements are now analysed from a bioenergetic, holosomatic and multidimensional perspective. Composite. While presented here in isolation for the sake of analysis, in the ceremonies the elements come together as a composite whole, creating an atmosphere of purposeful, highly charged thosenes, sometimes over several days of intent ceremonial activity. Arm Movements to direct clouds Example. “Then a bundle of emu-feathers tied together ... is thrust out towards a cloud and drawn (or waved) slowly back towards the operator. This is repeated many times (when another cloud is selected for a similar operation ...) to bring all the clouds together, then “big fella rain tumble down”. (Reid, 1930; cf. also Cherbury, 1932; Mathew & Anau, 1991) Auric coupling. The intraphysical consciousness (the rainmaker) is consciously promoting an auric coupling [i.e. a connection] between the hydro-energies of the clouds and his own bioenergies and using his energies as a lever, to will the movement of the clouds. Control. Consciousness can control energies and as we develop our holochakra and our ability to perceive and focus on energies beyond the soma, we can consciously extend our sphere of influence; for better or for worse. Extraphysical assistance and projections Projective account. The following is the account of a projection to produce rain, recorded by the anthropologist Ronald Berndt among Wiradjuri people in western New South Wales. It is interesting to note the distinctly cultural elements of the projective experience as well as the universal elements such as the silver cord (maulwar cord), the importance of controlling emotions and the temporal incongruence: As informants stressed, it took a very clever doctor to go unharmed through the dangers which accompanied a journey to the world behind the sky, where the water-bags were kept. When it was necessary, and only then, a discussion would be held between the tribal elders, headmen and doctors as to the advisability of obtaining rain. A doctor would be chosen, and a particular time named when he would undertake his skyward journey. On the auspicious night, he would “sing” all the inmates of the camp, so that they would sleep soundly, and not hear any noise that he might make or cause. He would then sit away from the camp and “sing” the clouds down so that they were about fifty to sixty feet from the ground; so near were they that “the noise of birds and ducks could be heard.” He would then sing out his ‘maulwa(r) cord and send it vertically up towards the clouds; it “would be just like putting a pole up”. He would lie on his back, his head upon his chest, with legs held up above the ground; in this way, watching the cord he would “sing” himself up. As the cord moved upwards past the clouds, it lifted the doctor who was suspended “like a spider.” Coming to Wantangga’ngura he let his cord gradually return to his body and standing upright looked around. He could see the darkness of the night sky, and all the stars, which were the various Ancestral Beings who had in the past climbed up here; being so close to them he could see their human form, whereas from the earth they appeared merely as points of light of varying brilliance. But he did not look long, since he was still outside the place in which the water-bags were kept; this place was called ‘Pali:ma, and was in the Wantangga’ngura country. To pass into Palima, the doctor had to go through a fissure, through which the Ancestral Beings had passed when they left the earth. This fissure or cleft was termed ‘mupara:m (...), and its two walls were continually moving around; this was demonstrated by the informant who used the open palms of both hands, placed them together, and rubbed them in a circular manner. The revolving of the ‘mupara:m left a small aperture which was revealed at intervals; it was through this latter that the doctor had to pass. ... Watching the revolving ‘mupara:m till an aperture appeared, the doctor entered and found himself in Palima, a country much the same as the earth, having also a sky above it. As he walked to and fro, looking around for the hut in which were stored the water-bags that had been sent up by the Eaglehawk, two Ancestral Men called Ngintu-Ngintu and Kunapapa ran up. Both carried clubs. The former began to call out a volley of questions, endeavouring to discover why the doctor had made this journey and entered the ‘mupara:m; but the “clever man” would not answer his questions, since otherwise he would be thrust out of Palima. Before Ngintu-Ngintu and Kunapapa were near, the doctor stopped walking – they must not see him doing this for if they did they would kill him at once. Coming up close to the “clever man”, who now sat down, they began to corroboree. They would dance and sing in the most humorous way, their intention being to make their onlooker smile, laugh or talk; should he do any of these things they would kill him. They danced with their legs well apart; their very long penes waved from side to side, and with the motion of the dance became erect and moved up and down; the doctor did not even twitch his lips. Then with their hands they made as if to poke out his eyes, but the other did not flicker an eyelid. They stared at him, coming close up and looking into his eyes; but still he did not blink or smile. After a while, Ngintu-Ngintu and Kunapapa became tired of receiving no response on the part of the doctor and sat down to one side. Then some women came up and began to corroboree in front of the doctor. They danced in an erotic manner, shuffling along with legs apart and knees bent; as they came close up to the “clever man”, they assumed an inviting posture and acted in other erotic ways. The doctor, however, still remained immobile; if he had been affected by, or if he had made any movement towards the women, he would have been killed. At last the women joined Ngintu-Ngintu and his companion and began to talk amongst themselves, each asking the other what could be done with the doctor. While they were thus engaged the latter “sang” away all of them except Ngintu-Ngintu, who was too powerful to be disposed of in this manner. Then taking out of his small skin bag a ‘nginbaran (emu anus-feathers tied in a bunch) he threw it into the distance and began to sing. The singing created from the bunch of feathers an emu; as the bird became visible the doctor called out to Ngintu-Ngintu ... : “There goes an emu”. Ngintu-Ngintu who was a keen hunter, gathered his spears together and rushed in the direction of his hut, in order to get his dog. While he got his dog, which went after the emu, the doctor sprang up and darted across to the hut in which the water bags were stored. Once there he speared one of the water-bags; as the water spurted out the doctor ran over to the ‘mupara:m in order to escape. However, Ngintu-Ngintu and his dog, who had found out that the emu created by the doctor was not of material substance, saw him running, and saw the water from the bag flowing to the fissure. The dog rushed over to the doctor, and snapped at him urged on by Ngintu-Ngintu. But the clever man reached the mupara:m unharmed; he escaped through it, and just as the dog put his head through it he “sang” the mupara:m closed (i.e. he stopped it revolving). When “he got well out of sight of the dog he sang the mupara:m loose (i.e. open)”. As it opened the water gushed out; because it had been kept in the skin bag since ‘ngerka:nbu times, the water was “stinking” and bad. When the doctor got the water “on this side” (i.e. out of Palima), he “sang” all the clouds up; into these poured the water, to be sieved and purified into clear water, to come down as rain either at once or a little later on. He then “sang” out his cord, and “climbed” down towards the same place from which he had gone up. The next morning he would say to the others: “See it is raining now”, or “It will rain soon”. His actual journey was said to have taken no more than a few seconds (Berndt, 1947, pp.361-363). Implicit. Aboriginal people often imply the importance of extraphysical consciousnesses in rain making by statements that claim that the success or failure of a ceremony depends on the co- operation of certain Dreaming ancestors. Extraphysical consciousness. Although it is not possible here to illustrate the role of extraphysical consciousnesses in weather phenomena, I do accept Vieira’s theory that they play some role in all natural phenomena (Vieira, personal comment during the course “Sensibilização Energetica”, Foz de Iguaçu, 1997). Evocation Imitation. Ceremonial participants will imitate the calls and actions of creatures related to water, such as ducks, fish, frogs, pelicans, swans and others. Such acts serve to focus the mind of the participants and evoke the atmosphere during which such creatures are usually encountered. Ceremonies. Feathers are a key ingredient to many ceremonies, being one of the few traditional items for creating “costumes” or for general adornment. Using the feathers of water birds may serve to establish an energetic link with those creatures, and by implication their moist habitat. Human Blood Sacrifice. Many agricultural societies sacrifice the lives (soma) of animal and even human intraphysical consciousnesses in their rituals, in the belief that this will please the Gods and make them grant a desired physical outcome, for example rainfall. It is possible that there were extraphysical consciousnesses associated with those rituals who would indeed see that the wishes of the intraphysical sacrificers were fulfilled. Pathology. The actions of the intraphysical and extraphysical consciousnesses in such cases are pathological to the extreme. Sacrifice of that kind is a social institution based on energetic vampirism of the life energy of the intraphysical victims. While it may bring immediate results during one intraphysical life, it leads to multi-existential stigmas and groupkarmic interprison. Bloodletting. Human blood is used in many Aboriginal ceremonies, but neither human nor sub-human animal is killed. The individual sacrifices from him or herself. Usually men will tie their upper arms tightly with a ligature and open a vein in their lower arm. The blood is collected in vessels or applied directly to the bodies of other ceremonial participants. It is drunk or sprinkled on objects and is used as a glue to attach feathers, wood shavings or other forms of decoration. Power. From the Aboriginal perspective blood has various powers. Its external application or consumption is thought to energise. It is also considered to feed the Dreaming ancestors. From a bioenergetic perspective, a person’s blood is a very strong carrier of their holothosenic imprint. From a multidimensional perspective, blood can be a food for tropospheric extraphysical consciousnesses and its density may facilitate inter-dimensional psychokinetic (PK) phenomena. “Rain stones” and pearl shells Shells. Throughout the Australian Western Desert pearl shells traded from the north-west of the country are used in rain ceremonies (Berndt & Berndt, 1944; Mountford, 1962, p.138). A part of the shell is ground into liquid, blood or spittle, which is then either ingested or spat out in various directions. Ocean. The connection between the shell and water, in this case the ocean, is obvious. Rain Stones. In other parts of the country, clear crystals are used in a similar way. A certain area along the Birdsville track in northeastern South Australia used to be called “rain country” because it is prolifically covered in gypsum, the “rain-stone”. Moisture. One researcher notes that his Aboriginal informants “observed the water-absorber mineral gypsum, and, on perceiving moisture induced changes or deliberately moistening the gypsum to promote such changes, crushed the mineral to free the water spirit.” (Kimber, 1997, p.8) Amplification. Crystals form a part of many “magical” practices among indigenous and non- indigenous people, possibly for their capacity to amplify the bioenergies of the intraphysical consciousness manipulating them. Red ochre Energise. Ochre is an essential ingredient to almost every ritual practice among Aboriginal people. It is applied to the body and ceremonial objects and is thought to energise. Often, red ochre is considered the metamorphosed blood of Dreaming ancestors. Grounding. From the bioenergetic perspective, the geoenergies of the ochre would arguably ground the individual applying it. Songs and Chants Words. The power of words is used in most indigenous societies. In Aboriginal Australia there are songs for many ends. People speak of having been “sung” to describe the acts of sorcerers who sing harmful songs to hurt their victim. Healing also occurs through song. There are songs for every “sacred site” and through singing them the places are energised and “come to life”. There are songs for increase ceremonies, to attract a desired lover and to influence the behaviour of humans and other animals. There are songs to make rain and songs to cause drought. (e.g. Hume, 2002, p.94; Martin 1988, p.26, Strehlow, 1971) Rules. Because of their power, songs are transmitted according to strict social rules. Composers. Ceremonial songs are never considered the product of human composition. They are thought to be ancient, from the Dreaming and composed by the Dreaming ancestors. Songs are either handed down across intraphysical generations or are the result of revelations during projections in which intraphysical consciousnesses are given the songs by the extraphysical consciousnesses “from the Dreaming” (Poirier, 1996; Strehlow, 1971, p.260). Repetition. Arguably, their repeated use over millennia has increased the bioenergetic charge of the words and actions in the same way as that of objects is increased through repeated use (psychometry). Effects. That words and songs should have physical effects of the magnitude contemplated by Aboriginal traditions is not supported by conventional science. From a multidimensional perspective the source of their power could lie in:

Objects Tjurunga. Engraved stones and pieces of wood were used as ceremonial objects throughout Aboriginal Australia. Among the Arrernte speaking people of central Australia they are called tjurunga, and anthropologists often use that term generically. Individual. Different ceremonies and different places in the landscape have their own individual objects, only brought from hiding at the appropriate time. Like the songs, these objects are considered the product, or even the embodiment, of the Dreaming ancestors (extraphysical consciousness). Attention. During ceremonies, these objects are subject to close attention; they are handed from person to person with each individual consciously exchanging energies with the object. People will meditate on the objects and sing the appropriate ceremonial songs while contemplating them. Reinforce. Like songs, the objects seem to function as a connector to extraphysical dimensions, and a way of tapping into an old and powerful source of consciential energies that has been reinforced over generations. These energies are channelled towards specific purposes according to the designated function of the ceremony with which the tjurunga is associated. Water Water. Most ceremonies involve sprinkling, splashing or diving into water. In some cases, participants spit. The sympathetic element is obvious; participants are seeking to replicate rainfall to attract or induce the real thing. Summary. To summarise, a rainmaking ceremony is composed of a set of energetic, physical and mental actions designed to fully focus the consciential energies of the participating intra- and extraphysical consciousnesses. In some cases, the rainmakers use the more direct method of conscious projections to influence the weather from the extraphysical dimensions. Serene. The Homo Sapiens Serenisimus does not require a ceremony to influence the weather. He or she does it directly through his or her holosoma. (Vieira, 1994). Conclusion Deficiency. This study is deficient in that it is only based on theory, not practice. I have not personally attempted to make rain while writing this article. I have, however, witnessed an Aboriginal man sing a rain song and this lead to unexpected torrential rainfalls less than 12 hours afterwards, and I know of numerous similar stories from other fieldworkers. Experiment. It is tempting to suggest an experiment whereby groups of people gather and, after going through the standard mobilization of energies, spend 10 or 20 minutes focussing their group-energies on the desire to produce rain. Such experiments may be inappropriate, however, due to the magnitude of the system being manipulated. Disaster. Physical rainmaking experiments (cloud seeding) in western England, for example, are linked to disastrous floods that killed 35 people in 1952 (BBC News, 13.01.2003). Once rain begins to fall, it is not easily stopped. Timing. This may be why Aboriginal people were cautious in making rain and preferred to do it during the appropriate time, i.e. when rain was naturally expected. Rain would only be made on other occasions after careful deliberation. Superiority. It should be pointed out that this article does not assert that traditional Aboriginal society was somehow superior to our own, simply because of its active working with multidimensionality. Pathology. Just as the pathologies in our society are highlighted by the headlines dominating our media, so the pathologies of Aboriginal society are highlighted through the recurrent theme of malign sorcery and fear based social control. Cosmoethics. If the term “superiority” is meaningful at all, it is so only on the individual level, in reference to the level of cosmoethics manifested by the consciousness, whether intra- or extraphysical. Logic. This article seeks to logically explain something that I have not seen explained elsewhere. As I am not a rainmaker I cannot pretend to know all the answers or understand all the details. So please dear reader, let me know of any omissions, errors or lapses of logic, so that I can improve my argument in the future. References ANONYMOUS; How to Make Rain; newspaper clipping found in AA3, South Australian Museum Archives; not dated. ANONYMOUS; Rain-making by the Aborigines: Remarkable savage ceremony at Poolamacca in Newsletter of the Royal Australian Historical Society; Oct.-Nov. 1978. BERNDT, Ronald & BERNDT, Catherine; A Preliminary Report of Field Work in the Ooldea Region, Western South Australia in Oceania 15(2); 1944; pp.124-158. BERNDT, Ronald & BERNDT, Catherine; The World of the First Australians; Ure Smith, Sydney; 1964. BERNDT, Ronald; Wuradjeri magic and “clever men” in Oceania 17(4); 1947; pp.327-365. CHERBURY, Chas. P.; Rain-making in Western New South Wales in Mankind 1(6); 1932; p.138 COX, William E.; Can wishing affect weather; in I.J. Good (ed.) The scientist speculates; Basic Books, New York; 1962. DE MARTINO, Ernesto; Il mondo magico: Prolegomeni a une storia del magismo; Bollati Boringhieri, Torino; 1997 (1973). DUERR, Hans Peter; Traumzeit: Über die Grenze zwischen Wildnis und Zivilisation; Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main; 1985. ELKIN, Adolphus Peter; Aboriginal Men of High Degree; Queensland University Press, St. Lucia; 1994 (1945) FRAZER, James George (Sir); The Illustrated Golden Bough: a study in magic and religion; abridged by Robert K.G. Temple; Simon & Schuster Editions, New York; 1996 GODDARD, R.H.; An Aboriginal Rain-Maker in Mankind 1(3); 1932; p.84. HERCUS, Luise & KOCH, Grace; ‘A native died sudden at Lake Alallina’ in Aboriginal History Vol.20; 1996; pp.133-149. HERCUS, Luise; Tales of Ngadu-Dagali (Rib-Bone Billy) in Aboriginal History 1(1); 1977; pp.53- 76. HORNE, G & AISTON, G.; Savage Life in Central Australia; Macmillan and Co., London; 1924. HOWITT, A.W.; Native Tribes of South-East Australia; AIATSIS, Canberra; 1996. HUME, Lynne; Ancestral Power: The Dreaming, Consciousness and Aboriginal Australians; Melbourne University Press, Melbourne; 2002 KIMBER, Dick; Cry of the plover, song of the desert rain in Eric K. Webb (ed.) Windows on Meteorology; CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood; 1997; pp.7-13. LONG, Joseph K.; Extrasensory Ecology: A summary of evidence in Joseph K. Long (ed.) Extrasensory Ecology: Parapsychology and Anthropology; The Scarecrow Press, Metuchen, N.J & London; 1977; pp.371-396. MARTIN, Sarah; Eyre Peninsula and West Coast – Aboriginal Fish Trap Survey; South Australian Department of Environment and Planning, Adelaide; 1988. MATHEW, Aggie Pinu & ANAU, Jerry; The Rainstones inBoigu: Our history and culture; Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra; 1991. MCCARTHY, Frederick; Aboriginal Rain-Makers in Weather 8; 1953; pp.72-77. MOUNTFORD; C.P.; Brown Men and Red Sand; Angus and Robertson, Sydney; 1962 (1950). NELSON, Roger D.; Wishing for good weather: a natural experiment in group consciousness in Journal of Scientific Exploration 11(1); 1997; pp.47-58. PEILE, Anthony Rex; Body and Soul: An Aboriginal View; Hesperian Press, Carlisle; 1997. POIRIER, Sylvie; Les jardins du nomade; Lit Verlag, Münster; 1996. RADIN, Dean; The conscious universe: The scientific truth of psychic phenomena; Harper Edge, San Francisco; 1997. REID, C.W.; A Note on Aboriginal “Rainmaking Ceremonies” in Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society (SA) 30; 1930; pp.80-82. ROSE, Debbie; When the rainbow walks in Eric K. Webb (ed.) Windows on Meteorology; CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood; 1997. STREHLOW, T.G.H.; Songs of Central Australia; Angus and Robertson, Sydney; 1971. TONKINSON, Robert; Nga:wajil: A Western Desert Aboriginal Rainmaking Ritual; PhD Thesis University of British Columbia; 1972. TREZISE, Percy; Rain-making sites in the Mosman River Gorge; unpublished manuscript; 1985. WARNER, W. Lloyd; A Black Civilization: A social study of an Australian tribe; Harper & Brothers Publishers; 1937. WHITE, Isobel; Rain ceremony at Yalata in Canberra Anthropology 2(2); 1979; pp.94-103. VIEIRA, Waldo; 700 Experimentos da Conscientiologia; Instituto Internacional de Projeciologia e Conscienciologia, Rio de Janeiro; 1994.

0 Comments

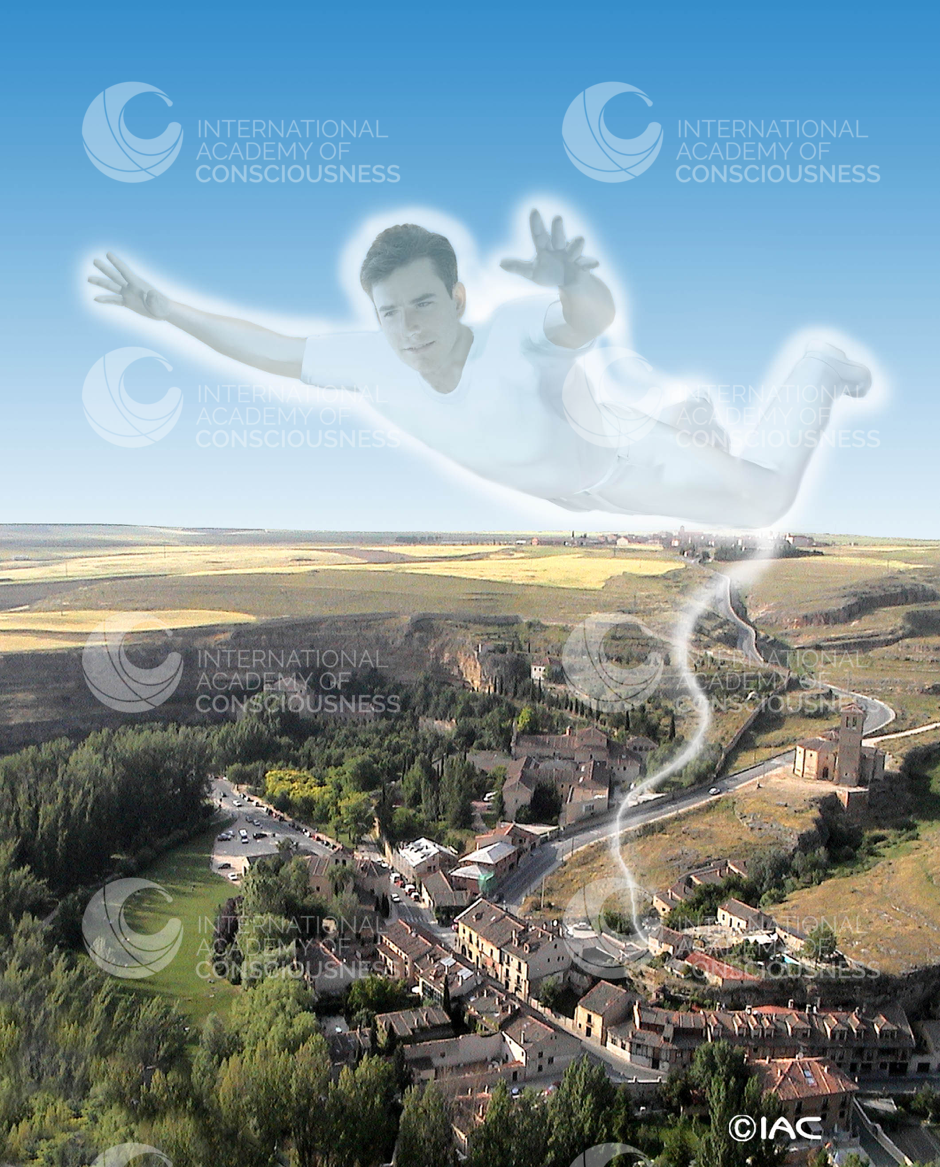

Given our current technological limits, subtle phenomena such as out-of-body experiences, encounters with non-physical beings or the existence of other dimensions of life are not readily proven in ways that will satisfy skeptics who have not had their own experiential proof. Apart from pursuing our own experiences, for now all we can do is collect, compare and analyse the experiences of those who claim to have travelled beyond the body. Surely consistencies in a substantial body of personal records at some point counts as evidence for the veracity of the accounts. One of the reasons I find corroborating evidence from Aboriginal Australian culture so compelling is that we know that Aboriginal people were largely isolated from other cultures for at least 10,000 years (since the last major ice age), and possibly much longer than that. Accounts by self-proclaimed multidimensional travellers from Europe, Asian and Africa may all have influenced each other, as pieces of the different esoteric religious traditions found across these continents were exchanged over the last two millennia or longer, and subsequently influenced more contemporary modes of spirituality. But Australian Aboriginal people had no such influence. So when their accounts of out-of-body travel corroborate what people from elsewhere in the world are saying, it suggests strongly that these diverse people are describing an objective reality, rather than a fantasy that coincidentally happens to be the same across the world. In this article, I look at one particular and often elusive feature of the out-of-body experience, an energetic link between the physical body and the non-physical body known as the “silver cord” by contemporary OBE researchers. I present evidence relevant to this “silver cord” found in the records of anthropologists who worked with Australian Aboriginal people in the first half of the 20th century. In particular, I draw on the research assembled by A.P. Elkin in his classic Aboriginal Men of High Degree and on an ethnographic account collected by a German anthropologist called Helmut Petri in the Kimberley region of Australia in the 1930s and published in a book called The Australian Medicine Man. Both Petri and Elkin recorded a number of accounts of out-of-body travel, including references to some kind of cord that was used by people to leave their body and travel in the sky. This cord sounds much like the "silver cord". The silver cord is the name given to the subtle energetic connection between our physical body (soma) and the body with which we manifest in non-physical dimensions (psychosoma or astral body). It is one of the more ambiguous features of out-of-body travel, because while some people report seeing it, there are many others who have had lucid out-of-body experiences but have never seen it. Nonetheless, the general consensus in the OBE community is that when we are projected outside of the physical body, the silver cord connects us back to that body. It acts as a kind of conduit of energy and sensory information between the two and, among other things, ensures that we always end up back in our body after an out-of-body experience. When we “die”, the silver cord breaks and our subtle body (psychosoma) loses its connection to the physical body. Robert Monroe and Waldo Vieira were two prolific projectors who both left written accounts of their perceptions of the silver cord. In his classic Journeys out of the Body, Monroe writes the following: I turned to look for the "cord" but it was not visible to me; either it was too dark or not there. Then I reached around my head to see if I could feel it coming out the front, top, or back of my head. As I reached the back of my head, my hand brushed against something and I felt behind me with both hands. Whatever it was extended out from a spot in my back directly between my shoulder blades, as nearly as I can determine, not from the head, as I expected. I felt the base, and it felt exactly like the spread out roots of a tree radiating out from the basic trunk. The roots slanted outward and into my back down as far as the middle of my torso, up to my neck, and into the shoulders on each side. I reached outward, and it formed into a "cord", if you can call a two-inch-thick cable a "cord". It was hanging loosely, and I could feel its texture very definitely. It was body-warm to the touch and seemed to be composed of hundreds (thousands?) of tendon-like strands packed neatly together, but not twisted or spiralled. It was flexible, and seemed to have no skin covering. Satisfied that it did exist, I took off and went. (p.175) Vieira provides an account with some parallels and some subtle differences in his Projections of the Consciousness: A diary of Out-of-Body Experiences. After having examined his own psychosoma closely during a projection, Vieira writes: To conclude the "physical" inspection of the psychosoma, I raised the right hand to my back, head and neck, and once again very closely examined the "skin" of the neck region and the silver cord. It again impressed me as being a combination of tiny, loose cords or fine, occasionally sparkling elastic strings, firmly attached to the psychosoma. The silver cord exhibits warmth, flexibility and the texture of human tissue. It has a structure and nature closer to that of the psychosoma than to that of the soma. The energetic filament does not seem to stop at the skin. it gives the impression of entering the soma and establishing a deep connection with one or more vital centres. Could one of them be the pineal gland? How can such an apparently fragile structure have such a powerful flow of energy? While I deeply pondered the fact, as if engaged in an internal monologue, I held the silver cord close to the soma and activated the return system by pulling on this appendage. In seconds, I was consciously diving into the physical body. (p.86-87) The images below (courtesy of the International Academy of Consciousness) give you a sense of how the silver cord connects the physical body to the non-physical body (psychosoma). When we are close to the body, it is said to be quite thick and have a substantial pull, making it one of the obstacles of us leaving the body with full awareness. As we move further away it becomes very thin. Seemingly there is no limit to its stretch and reach as we project around the world, to other planets and other dimensions. In Aboriginal Australia, the ability to leave the physical body consciously is usually grouped with other psychic abilities, such as clairvoyance, the ability to communicate with and influence non-physical beings and the ability to manipulate energies. Only some people develop these abilities and such people are often referred to as “clever” (see my blog piece on the use these clever men and women make of out of body travel). Clever people, men or women, are usually “made” through processes of initiation involving a range of spirit beings. In other words, there are culturally acknowledged steps by which a person comes to develop these psychic abilities. In their respective books, both Elkin and Petri draw on their own field work from the 1930s and ‘40s, and survey earlier accounts from other researchers of the way clever people were made across Australia. When reading these accounts, it is important to be mindful of a number of factors likely to have impacted the way they were recorded: basic linguistic issues, i.e. the English language proficiency of the Aboriginal informants and the Aboriginal language proficiency of the anthropologists; the anthropologists’ ideas about reality and how that may have influenced how they heard their informants; the Aboriginal ideas of reality and how that lead them to express themselves, for example it has been my experience that Aboriginal people do not necessarily make an explicit distinction between the categories of physical and non-physical as most Europeans do, because they do not experience the two as separate. I think it likely that all these factors played into the record of the following account documented by Elkin from New South Wales: During their making in south-east Australia, a magic cord is slung into the doctors. This cord becomes a means of performing marvellous feats, such as sending fire from the medicine man's insides, like an electric wire. But even more interesting is the use made of the cord to travel up to the sky or to the tops of trees through space. At the display during initiation - a time of ceremonial excitement - the doctor lies on his back under a tree, sends his cord up, and climbs up it to a nest on top of the tree, then across to other trees, and at sunset, down to the ground again. Only men saw this performance, and it is preceded and followed by the swinging off the bull-roarers and other expressions of emotional excitement. In the descriptions of these performances recorded by R.M. Berndt and myself, the names of the doctors are given and such details as the following: Joe Dagan, a Wongaibon clever man, lying on his back at the foot of a tree, sent his cord directly up, and "climbed" up with his head well back, body outstretched, legs apart, and arms to his sides. Arriving at the top, 12 meters up, he waved his arms to those below, then came down in the same manner, and while still on his back the cord re-entered his body. Apparently, in this case, his body floated up and down in the horizontal position with no movement of his hands or legs, and the explanation must be sought in group suggestion of a powerful nature. (Elkin 1977 p.54-55) For someone who has studied the projection of consciousness and other psychic phenomena this account can be interpreted in ways that are unlikely to have occurred to Elkin. For example, from such studies we know that the silver cord is closely related to the energetic body (energosoma, pranic body), which is constituted of the subtle energy also known as Chi/Qui. When this energy is highly developed, it is often experienced as “fire” or electricity, leading to intense heat within the person’s body which can also be externalised to others.

Elkin seems to have interpreted the account of the person travelling up to the trees on the cord as if it was the person’s physical body that flew up to the top of the trees and then returned. However, it seems much more plausible and from a multidimensional perspective perfectly logical, that it was in fact the non-physical body (psychosoma, astral body) that flew up to the top of the tree while the physical body would have remained prone on the ground with the silver cord connecting the two. From that perspective, the doctor was showing off his skill of lucidly leaving his body, while the audience was able to see both the silver cord and the psychosoma; this was the fascinating bit and the part Elkin’s informant focused on in relating the event, without making explicit the distinction between physical and non-physical. This seems especially plausible to me, as I have never seen my own silver cord, but when running OBE workshops have seen other people’s silver cords and psychsomas as they projected and therefore have a sense of what that might look like. Later in his work, Elkin discusses that some of the seeming variation in the making and practices of doctors (or clever people) may actually be the result of incomplete data. Speaking about the “magic cord” he explains that, … up to 1944, their use of cords, aerial rope, was reported only from Victoria and inland New South Wales, but since then I have recorded it from the north coast of the latter state, for the Gladstone and Cloncurry districts, respectively in coastal and far inland Queensland, and in this chapter for Dampier Land, southwest Kimberley, Western Australia. Possibly, it was also a psychic phenomenon displayed by members of the craft in tribes in between. (Elkin 1977 p.180) In other words, this “magic cord” was reported from people across Aboriginal Australia as involved in people’s ability to fly. An even clearer account of the silver cord in Aboriginal culture comes from Helmut Petri, a German anthropologist who first conducted fieldwork in the Kimberley region of Australia in 1938. Like Elkin he was interested in the social role and asserted abilities of the clever people, who he called medicine men. One of their abilities that he documented was to go on “dream journeys”: During the dream journey the ya-yari roaming in the distance remains connected to the body by the thin, fine thread, and when it returns it is accompanied by the agula to just outside the doctor's camp. (Petri 2015 p.13) In the language of the Unambal with whom Petri was working, the ya-yari is the psychosoma or non-physical body of a living person, while the agula is a deceased person. This suggests that what Petri here calls “dream journey” is really a visit to a non-physical dimension where the person who is projected during sleep meets deceased people, who in this case accompany him back to his body. In analysing the differences and parallels of two kinds of “doctors” (ban-man, who are the classic doctors of the Unambal people, and “devil-doctors” who are a new kind of doctor who emerged since colonization through the introduction of new ceremonies), Petri again refers to the cord: The Devil Doctor has in common with the genuine ban-man the gift of miriru, i.e. he can work himself into states of trance or vision and visit the realm of the spirits. He too releases his ya-yari from his body. The ya-yari then is said to go up a tree and travel along a thin, fine thread to the distant island of the dead, Dulugun, or into the celestial beyond on the other side of the Milky Way. Some agula will escort him and see to it that he returns safely again to this world. (Petri 2015 p.26) The agula, or extraphysical consciousnesses mentioned here appear to be helpers, assisting the doctor in his projection. It seems clear from these brief accounts that the Unambal people knew of the silver cord that connects the psychosoma and the body. Like Elkin, Petri also surveyed the literature relating to other parts of Australia and reproduced several other references to cords associated with extracorporeal travels. There is a reference to the Mara tribe from the Gulf of Carpentaria, whose doctors “go on journeys to the sky. At night time and invisible to everybody, they will climb up into the sky on a rope in order to hold converse there with the people of the star world. (Petri 2015 p.104). And writing of the Kurnai people from New South Wales he said that Kurnai belief that doctors ascend to sky by aid of a rope and that their neighbours shared their beliefs that their doctors "climbed into the sky on threads, as thin as blades of grass " (Petri 2015:113). In summary, it is in my view clear that Aboriginal people from across Australia have known about the energetic connection, the “silver cord”, between the physical body and our subtle body for thousands of years. This is important data, because Aboriginal culture has not received influences from other cultures for a very long time. As such the fact that Aboriginal people describe this connection in ways very similar to the accounts of more contemporary European researchers supports the objective reality of this energetic “body part”, or perhaps better “para-body part”. There seems to be, however, a cultural difference in the emphasis given to the cord. In the European esoteric traditions, the silver cord is emphasised as the connection that ensures our return to the physical body, whereas in the account collected from Aboriginal people the emphasis seems to be on it as a tool or mechanism that allows exploration away from the body. Given the many other cultural differences, this is hardly surprising. 17/2/2014 The therapeutic use of the projection of consciousness and other psychic phenomena among the shamans of Central AustraliaRead NowThe texts below are direct translations of accounts provided in their own language by three Central Australian shamans, referred to commonly as “traditional healers” or “clever people” in Aboriginal English and as ngangkari in the native Pitjantjatjara of the authors. In these accounts the three healers explain their conscious use of the projection of consciousness and clairvoyance in their healing work. They explain the multidimensional aspects of their healing work; how they fly around at night (OBEs) helping their community, and how much of their work focuses on the spirit (psychosoma) of their patient. Australian Aboriginal culture is often described as the oldest living culture on Earth. Before European colonization 200 years ago, the people on the continent had been largely isolated from other cultures for thousands of years. The archaeological record agrees conservatively that Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for at least 50,000 years, seemingly with little cultural change. In most parts, the last 200 years of colonization have caused substantial cultural loss. But in some of the more remote areas, English is still a second (or third or fourth) language and people still live in accordance with their own cultural priorities. The Pitjantjatjara people of the central deserts of Australia are one such remote group. The texts give us a glimpse into a multidimensional understanding that has existed for thousands of years, long before the canonical texts of the Judeo-Christian religions, the European esoteric traditions, the “New Age” movement, or the technical explorations of OBEs that started last century. As such they are a powerful piece of evidence for the universal nature of the projection of consciousness. The texts originally appeared in The Australian newspaper and are extracts from a book about the ngangkari called Traditional Healers of Central Australia: Ngangkari published by the NPY Women’s Council. FLYING spirits, sacred tools, treatment by touch ... the traditional healers of central australia explain their extraordinary skills. NAOMI KANTJURINY

I was only a teenager when I received the gift, which initially scared me! This power just came to me alone. I'd wander around at night with my powers, and return to my camp early in the morning. All I could think was that I must have become a ngangkari [traditional healer] for some reason. I asked my mother, "Mother, why do I drift around at night so much?" and she replied, "You must be a ngangkari then." My reaction was, "What?" and she said, "Yes, it seems that you have become a ngangkari all by yourself!" We say wirunymankula waninyi - which means, to declare someone well and to banish the illness. The illness, or pain, can take the form of phlegm, or back pain, and this is what I specialise in. My work was as a healer, mostly helping women and children. Very often they didn't need to tell me what was going on, because I'd know already. So I'd give the appropriate treatment and I know they were good. Women and children were healed by me countless times, especially children. In Ernabella [mission, in far northwest South Australia], people would go and see the white doctors after they'd seen a ngangkari. They'd tell the doctor they'd seen a ngangkari already and the doctors encouraged this, because it made people stronger. The white nurses would be happy as well. The only difference was, they were on a salary and I was not. I would tell them that I didn't get paid for my work. Ngangkari have always worked for free. The touch of my hands has a healing effect. I give a firm, strong touch, and remove the pain and sickness, and throw it away from the sufferer. After their treatment they will stand up and tell me how they feel and, of course, there is always an improvement. At night I see spirits. The kurunpa spirits talk to me. Spirits separate from the body when someone is unwell or suffering and I see them. This is how I find out they are not well. I have dog friends that help me, as well. These dogs are my friends. At night I travel around by myself to make sure the women are all right. I see everyone at night, how they are, if they are all right. Sometimes it scares me but it is my work, I have to do it. I travel alone and that is what I do. Depressed people can feel a lot better within themselves after a ngangkari treatment. That's one of our specialities. Their spirits are out-of-sorts, and not positioned correctly within their bodies. The ngangkari's job is to reposition their spirits and to reinstate it to where it is happiest. Some people ask me how I do the treatments that I do. I tell them that I have unique skills that are not easily explained, which I developed by myself. After a treatment, it is our task to ensure the sickness doesn't return and pain doesn't return. So we have to dispose of the pain in our special way. Ngangkari know how to do this. We have special powers in our hands. Our work is to mould the shape of the body so that it can accommodate the spirit properly. In that way, people are well. I ask people afterwards, "Are you feeling better now?" and they tell me, "Yes, I am feeling great!" Ngangkari touch people. We touch, and that is our special art and our skill. ANDY TJILARI When I was growing up I had three grandfathers who were all ngangkari: my mother's father, my father's father and my grandfather's brother. So I lived with these three ngangkari. Well, actually there were four, because my father was a ngangkari as well. One day my grandfather asked me, "Do you want us to give you ngangkari power, so that you can live your life as a ngangkari? You'll have to help sick people, and heal them, whether they are men, women or children. If you do become a ngangkari, the power will stay with you all your life and you'll never lose it, or be able to throw it away." My father was observing all of this. He told me that the way I would have to heal people would be to pull the sickness out of their bodies in the form of pieces of wood, or sticks, or stones, things like that. This is so that people can actually see with their own eyes the sickness that is removed from their bodies. This is the commonly accepted way we ngangkari do our work. It is so that people can see us taking their sickness away from their bodies, which gives them a sense of removal. My father told me I'd have to make sure I showed them what I took out, so they could see it, before I disposed of it. I said to my father, "But how? How am I supposed to do that? I don't understand how ngangkari work. How could I ever be able to do that?" He replied, "Don't worry, we'll show you. It won't be hard once you know how." So I was shown. I was given the power of a ngangkari by all my grandfathers, and I still have that power today. They taught me everything I know. They didn't tell me how to do it. They showed me. They also placed inside me the sacred objects I would need to be my tools for working as a ngangkari. These are called mapanpa. In the past, many children became ngangkari at a very early age. Children who took an interest in the healing arts often asked to be given power and to receive training. Often this training took place, as it did for me, at a distance from camp. The ngangkari would light fires at a separate camp and they would wait for the spirits to bring them special powerful tools. During the night, when they were all asleep, all the ngangkari people's spirit bodies would start to rise up from their sleeping bodies and soar upwards. Now you know how people fly around in aeroplanes and drive around in cars? Well, for Anangu [people of the Western Desert], and for ngangkari, when they are asleep at night, their spirits move around in a similar kind of way. The ngangkaris' spirit bodies begin to fly around and to visit the sleeping spirits of other people to make sure all is well. The spirit of a sick person is usually too sick to fly properly, and often crashes into trees. This is when the ngangkari's night time work is very useful, because they will see the injured spirit holding onto the trunk of the tree, or fallen on the ground. The ngangkari will rescue the spirit. In doing so, he is able to recognise who it is and will say, "Oh, this is such-and-such. He is not well. Poor thing, he needs help here." So he'll pick up the spirit and take him to the body and ask the sleeping person to wake up. "Wake up. Your spirit is not well. Sit up and I'll put you to rights." The person will sit up, the ngangkari will replace the stricken spirit, and all will be well again very soon. By the next day, he will be quite better. This is a very special skill which we ngangkari alone have. While all the ngangkari are gathered in the special camps, hundreds of mapanpa will come flying in. Mapanpa are special, powerful tools. They hit the ground with small explosions, "boom, boom, boom!" The ngangkari dash around collecting up the objects: kanti that look like sharp stone blades, kuuti that resemble black shiny round tektites, and tarka - slivers of bone. Each ngangkari gathers up the pieces he wants. These pieces become his own property. I realise all this sounds very different to all you doctors and nurses who worked so hard at university to get where you are today. You have studied so many books. But we are working towards the same goal of healing sick people and making them feel better in themselves, as you are. In that way we are equal. MARINGKA BURTON My father had been a ngangkari his whole life, and his mapanpa had been given to him by his father. When he finally did give me the mapanpa, I became mara ala - meaning, my hands became open, my forehead became open, and I could see everything differently. I was able to travel into the skies with other ngangkari, soaring around in the sky, travelling great distances, and coming back home in time for breakfast. Ngangkari travel around in the sky, just our spirits travelling, while our bodies remain sleeping on earth. My father taught me that. He taught me everything, carefully and slowly. We used to go for holidays a long way from the communities, and the white people used to follow us with the ration truck to give us our food ration in exchange for dingo scalps. All that flour and food! Sugar, sweet tinned milk, golden syrup and tins of meat. I know that a lot of our people are on dialysis now. It is from that sugar we ate back then. We all know this now. It is a shame because we have always had wonderful traditional bush foods. We had all the bush medicines that were used by everybody, it wasn't part of the ngangkari's specialised work. We used the bark on the roots of the wakalpuka bush for a splint if a child broke their leg or arm. We'd put the skin of the nest of the itchy caterpillar onto burns and itchy sores; you take the nest and remove all of the droppings from the inside of the nest and wash it and then you put it on the skin. It was a fantastically good treatment for burns, rather like doing a skin graft! If somebody scratched and itched, we'd put it on that as well. My mapanpa live in my body. I am a painter, and when I paint, my mapanpa move right up into my shoulder and sit up there, out of the way. If somebody comes to me, needing help, I would have to ease my mapanpa back into my hands again. Sometimes I would push them from one arm to the other. When I am giving a healing treatment, I push with my left hand and I extract with my right. I work on the head a lot and I heal people if they've got a headache. If there is something serious like a car accident and we are called to attend, we go straight there without delay. People have been hurt and the terrible shock of an accident shakes the kurunpa [spirit] out of a person and so we go there to find the kurunpa and we bring it back and replace it. Without the spirit any bodily healing takes much longer. Afterwards we attend the clinics, and when they call us, we do our work courageously without fear. In the past non-Aboriginal doctors would do their work, yet they didn't know about us traditional healers. Our traditional healers were always busy healing people at home, looking after the entire community, while the doctors did their work in their clinics. But neither knew how the other one worked. We are unable to do too much work with renal patients; we never touch their kidneys, they are too vulnerable. But we do help with pain and discomfort. Dealing with the deceased, sometimes we can capture the spirit of the deceased and place it into the living spouse, which is a really caring and strengthening thing to do. Sometimes if a son passes away, and the mother is really sick and bereaved, the dead son's spirit is placed inside the mother. In that way everybody is happier and it ensures that they get back to their normal health more quickly and are happier and healthier during their time of grief, because it is really terrible if somebody is too sad for too long. Sometimes I can call a spirit with a branch. Using the branch I can usher it along, into the burial place, where the spirit should be. Sometimes the spirit will leave the body and leave the burial ceremony and travel around and make people sick. Sometimes, if I see that, I use a branch to brush it along, to brush it along so it goes back to the cemetery. See here on my elbow? That's where my mapanpa sits. I've got openings in my hand and an opening in the forehead. We say that ngangkari people are mara ala and ngalya ala, which means open hands and open mind. When you hear someone say, "Oh, he's mara ala," that just tells you instantly that she's a healer, a traditional healer, a ngangkari. Traditional Healers of Central Australia: Ngangkari (NPY Women's Council) is out now, $49.95. 25/8/2013 Expanding the boundaries of reality: parateleportation in the Western Desert of AustraliaRead NowEarlier this month I had the opportunity to participate in a fascinating conference panel at the 17th World Congress of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. Panel sessions explored mediumship, spirit possession, depression and others issues from an anthropological perspective. All presentations can be heard under the Events tab on the website of the Afterlife Research Centre. My paper looked at a phenomenon in which people are allegedly transported from one location to another by non-physical means. In the research literature this phenomenon is sometimes known as parateleportation and it has frequently been reported by Aboriginal people of the Australian Western Desert area. I am making a written copy of the conference paper available here.

Pushing the boundaries of reality: Accounts of parateleportation among Western Desert Aboriginal people Paper presented at the 17th World Congress of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, Manchester 2013 to the panel WMW13 The extended self: relations between material and immaterial worlds This paper is essentially about paradigms and genuine scientific engagement with things we do not yet understand. It reflects my strong view that anthropology can make significant contributions to our understanding of consciousness and the full spectrum of the human experience. There are two key aspects that strongly position anthropology to make such contribution in my view: first is our relationship with peoples whose paradigms of the world are not confined by materialism and who instead view life to include both physical and extraphysical dimensions. In other words, we are consistently confronted with experiences and world-views that challenge us to go beyond our own cultural preconceptions. Second, is the requirement of our positioning as cultural translators, to not simply accept the paradigms and interpretations of our informants, but continuously seek to distill universal human principles that underpin cultural variation, and thereby develop new models of understanding the human experience. I have on previous occasions focused on the out-of-body experience (projection of consciousness, astral projection) as a significant area of research (e.g. McCaul 2003, 2008). Not only does that experience go to the heart of our understanding of life beyond the physical dimension, but it is also both ubiquitous among indigenous cultures (Sheils 1978) and potentially achievable by the anthropologist. This latter aspect is relevant not only from our own disciplinary priority of participant-observation, but also means that the experience can be explored “from within” in accordance with Charles Tart’s proposal of state-specific sciences (Tart 1998). A full understanding of the OBE profoundly challenges the conventional materialistic paradigm and challenges us to develop new models of understanding reality (unless of course we seek to explain away the significant data about the experience from a position of fundamentalist reductionism). This again advocates that there is a need for a broader paradigm if we want to genuinely understand the full range of experiences of consciousness, but the experiences it draws on are, in my view, of a different order than the by now very extensively reported and documented OBE (Vieira 2002). It was prompted by accounts of seemingly impossible human feats from among Aboriginal people of the Australian Western Desert region. They were the type of accounts that most non-Aboriginal people who heard them would smile at benignly while “knowing”, from within the security of their own paradigm, that they could be no more than “old wives tales”. If we move beyond that security, however, into the space of genuine scientific inquiry we need to consider whether these accounts are more than simple indications of cultural beliefs, but may in fact be pointing to an understanding of reality that reflects genuine experience rather than misguided tralatitious belief. Ethnographic Background Life beyond the physical dimension features strongly among Australian Aboriginal people. The benign and malign actions of spirits, the ability of old people to connect with creation ancestors in their sleep through out-of-body experiences, and the ability of humans to influence the natural environment through song and ceremony are all widely reported and well documented (Berndt 1947, Elkin 1977). Significantly for the phenomenon discussed here, song appears to be a methodology for interdimensional communication, i.e. a way in which physical people evoke and obtain particular assistance from extraphysical people. The ethnographic data for this paper is derived from the Western Desert of Australia. The Western Desert area is the largest homogenous cultural area in Australia stretching from just to the east of the coast of Western Australia at Broome to Oodnadatta and Coober Pedy in South Australia and from the Nullarbor Plain in the south to Yuendumu and Balgo in the north (see map). This vast area is marked by significant linguistic and cultural cohesion, argued convincingly by Berndt (1959) to reflect a single cultural bloc. This cohesion is expressed up until the present through significant mobility across this region including for the purpose of large ceremonial processes uniting people from the far-flung communities (Peterson 2000). The information discussed in this paper is from the south-eastern extent of this vast area, in South Australia where I have been working in Aboriginal affairs since 2000. The Western Desert area is one of the main bastions of traditional Aboriginal culture in Australia and widely known for its conservative approach to ceremonial business. Men from many other areas where ceremonies are no longer practiced regularly travel to Western Desert communities to “go through the law”, i.e. to achieve full classificatory manhood by going through initiation ceremonies. As well as maintaining what could be considered the bedrock of classical Aboriginal religious structures through the standard male initiation processes, the Western Desert is also one of few areas in Australia that continues to produce a significant number of traditional healers (Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council Aboriginal Corporation 2003). Known as ngangkari, at least in the eastern part of the region, these healers could be broadly considered as part of the shamanic spectrum with much of their healing focused on managing subtle energies and battling extraphysical consciousnesses (spirits). The phenomenon in the cultural context Soon after starting work with Aboriginal communities in South Australia I heard the story of Aeroplane George – a story that I have since heard in slightly different variations at least half a dozen times. According to this story, Aeroplane George earned his name for his uncanny ability to travel at seemingly impossible speeds. In all the versions I heard he was seen at one train station waving to people who had boarded a train, for example at Tarcoola. Next they saw him when they arrived at their destination, for example Cooper Pedy, waiting as the train pulled into the station. The specific stations in the stories varied, but the fundamental aspect of the story was always the same. And apparently it was not only Aboriginal people who experienced this. On his death in 1978 a newspaper reported that “many a tourist was puzzled at seeing George at Cooper Pedy and then upon arrival at Kulgera, they would be greeted by Aeroplane George. No one knows how George managed to travel so fast.” I already had an interest in so-called paranormal phenomena at that time and so I registered that story among many others involving spirits and out-of-body experiences, all of which seemed to be treated as common-place and natural by the Aboriginal people I spoke with. It was not until several years later, however, that I spoke with a Pitjantjatjara man called Murray, who actually claimed to have experienced what Aeroplane George had. After telling me about the making of a traditional healer and the significance of the out-of-body experience in his culture, he spoke about an experience he once had as a young man when some old men showed him and a group of youngsters something he referred to as walpa (“wind”). He described this as a skill that involved using an emu feather and certain songs, which allowed them to all travel from Ernabella to Alice Springs and back in 2 or 3 hours. A return trip from Ernabella to Alice Springs is about 660km through the desert as the crow flies. On this trip the group apparently passed through hills, cars and buildings. They went into a bank vault and saw all the money but were not allowed to pick any up. There were lots of white people there, but they did not see any of the Anangu (the term by which these Western Desert people describe themselves). Murray said that this was the skill Aeroplane George used. He said he and others were a bit ambivalent about this skill as it could be used to steal things or commit other crimes. In other words it had to be used with caution and could be dangerous in the hands of unscrupulous individuals. Despite my long-term interest in such matters, this account seemed quite fanciful to me. I had studied OBEs for many years, had met many people who had experienced them and had experienced my own. I knew that traversing matter is a common feature of those experiences. In that state it makes sense as the consciousness is using a body that is more subtle than physical matter and can therefore pass through it. So I double checked. Was he talking about travelling in his spirit body? No, he was very clear that this was not a “spirit journey”. His physical body had gone on this trip. It would have been easy to dismiss this experience as one step too far, but doing so would have been hypocritical. If I were to only accept those accounts I could relate to from a basis of personal experience, my position would be just another variation on the classic paradigmatic limitations of inquiry. And I should emphasis here that I am not advocating blind acceptance of all beliefs and accounts of experiences, but open minded and genuine inquiry. The Phenomenon I discovered that Elkin reported the phenomenon of ‘fast travelling’ in his classic and still unrivaled account of Australian Aboriginal shamanism (Aboriginal Men of High Degree, Elkin 1977) as occurring among numerous groups across Australia. He in turn drew parallels between the accounts he had recorded and accounts recorded from Tibet (David-Neel 1965). Clearly, the phenomenon was not isolated in its occurrence or simply the result of a localized delusion. I consulted the work of Vieira (2002), who focuses on the OBE, but nonetheless provides a comprehensive discussion of concomitant phenomena. Among them is the phenomenon he terms parateleportation, which he defines as follows: a phenomenon composed of dematerialization, levitation, apport and rematerialization, in which the intraphysical consciousness suddenly disappears and reappears in another location; the act or process of transporting objects, human beings or subhuman animals through space, without any mechanical means. (Vieira 2002:195) Vieira then identifies 24 frequent characteristics of this experience, including relevantly: