|

Preliminary Comments This article is more academic than most of the other fare on this blog. It previously appeared in 2005 in the Journal of Conscientiology, Vol.7 No.27:203-221, and it follows formatting conventions I used there. I have decided to reproduce it here to make it more widely accessible for a few reasons. One is that I regularly encounter questions about rainmaking and this usefully sums up my understanding on the matter. The other is that humanity's impact on the weather is becoming an ever more urgent issue. Addressing physical pollution is clearly a priority in this regard, but the importance of addressing our mental pollution cannot be underestimated. Our relationship with nature begins in our thoughts and emotions, and real life actions flow from them. The idea that we can control the weather with our energies, which are directed by our mind and intention, introduces a degree of consciousness and deliberateness that is largely lacking in our present society when it comes to the weather and climate. Despite all the ways western "civilisation" has domesticated nature, we feel as if we are at the mercy of the weather, while those in denial of climate change claim that our actions have no consequence. This is in stark contrast with indigenous approaches, where it is absolutely assumed that human actions have repercussions on the world around us and that humans can control the environment through conscious actions. As this article documents, those beliefs have been mocked by Europeans ever since colonisation began and there are plenty of people who still mock them. As I argue in this paper, although advanced in the name of science, such dogmatic ridicule is actually a completely anti-scientific approach. I would suggest that this is the point in history where we need to examine indigenous approaches again with fresh eyes and consider whether we can learn anything from them for the way we relate to and engage with the environment. Introduction Reality. In the 1940s, the Italian anthropologist Ernesto De Martino (1997) used the ethnographic literature to show that the “impossibility” of certain phenomena, such as telepathy and precognition, arises from preconceptions, not facts. Rainmaking is a case in point. Your underlying view of reality will determine whether you consider it possible for human consciousness to cause rain. Science. For mainstream scientific discourse, the idea that humans could make rain by force of will and, for example, singing and dancing is absurd. For most indigenous societies it is a given (cf. Berndt & Berndt, 1964, p.252). Record. Rainmaking ceremonies have been recorded across Aboriginal Australia (McCarthy, 1953). The quality and format of their descriptions varies widely. In many cases, recorders did not actually observe the ceremony, but were told how it should be done and what should happen. On other occasions, they attended the ceremony, but do not mention the outcome. Open Mind. Almost all reporters make some comments, which indicate that they did not approach the subject with an open mind, like the following:

Success. The evidence I have considered shows that not all rainmaking ceremonies are successful, but many accounts by anthropologists and other observers do speak of rain falling shortly after a ceremony (Berndt, 1947, p.365; Berndt & Berndt, 1944, p.133; Duerr, 1985, pp. 287- 288; Goddard, 1932; Hercus, 1977, pp. 69-71; Horne & Aiston, 1924, p.120; Reid, 1930; Strehlow, 1971, pp.434-436; White, 1979, p.99). Choice. Even when it rains, however, we have no choice but to adopt explanations of “coincidence” or “deceit” as long as we believe it impossible for human consciousness to act upon the weather. Analysis. The premises of the consciential paradigm enable us to accept the possibility that consciousness can affect the weather and consequently allow a functional analysis of Aboriginal ceremonies. Relevance. The relevance of such analysis goes beyond the explanation of a specific practice. Rainmaking is only one of numerous practices that arise within societies that prioritise multidimensionality. Such societies seek to manipulate the physical dimension through the power of consciousness in many areas of life; they are fundamentally multidimensional societies. Anthropological explanations Parrots. It is an accepted scientific principle to draw on research and conclusions of others. That can be reasonable, as there is no point in continuously reinventing the wheel. It becomes a problem when it leads to the parroting of badly obtained research results or prejudiced opinions. Heresy. The fact that a statement increases in authority with each repetition is observed in both popular (media) and scientific discourse. Repeating statements can lead to creating and re-affirming a consensus reality until stating a contrary view becomes an act of heresy that provokes ridicule or abuse. This is very relevant to the multidimensional study of consciousness, because such study is based on premises that have long, repeatedly and vehemently been declared impossible by the dominant scientific discourses. Working with those principles thus becomes an heretic act in the eyes of the wider scientific community. Anthropologists. Most anthropological studies of rainmaking suffer that crippling effect. With very few exceptions, they consider rainmaking an impossibility and because of that premise they do not spend any time looking at how it may work. Their premise itself is never questioned, because that would be heretical. Explanations. As a result, anthropologists have either not tried to explain successful rain making at all or they have chosen one of two explanations: 1. Perception. 2. Chance. Perception. The “perception” explanation is that the rainmaker is a particularly perceptive person who is aware of minute environmental changes which show him or her that rain is likely to fall in the near future. According to this argument, rain is only “made” when the signs of nature, perceived exclusively by the rain-maker, show that it is imminent. Culture. Researchers have commented on the remarkable, culturally encouraged, perceptiveness of Aboriginal people (e.g. Poirier, 1996, pp.189-190). There is no doubt that Aboriginal people who have grown up in the bush are more capable of foretelling future weather by environmental signs than most white people would be. Heightened perception and knowledge of nature is a general characteristic of traditional Aboriginal people. It is precisely for that reason that the perceptiveness argument is flawed. Signs. Both women and men, young and old are capable of seeing signs in nature, for example those that indicate the availability of natural resources (Rose, 1997). It is fair to assume that many traditional Aboriginal people will be able to notice signs of pending rain, not just the specialised rainmakers. Special. Consequently, it would not make sense for rainmakers to be accorded special status for making something everybody knew was coming anyway. Community. In societies where rainmaking ceremonies are complex communal processes, this argument lacks further logic. For example, in Howitt’s description of rainmaking among the Dieri (Howitt, 1996, pp.394-396) first the “great council” determines that it is time for such a ceremony, because of long lasting drought. Messengers are then sent out to the scattered camps to gather everybody together for a communal ceremony. Other authors also describe careful consultation (Berndt, 1947, p.361; Rose, 1997, p.4) and extensive ceremonies involving hundreds of people (Tonkinson, 1972; White, 1979). Clearly people are going to this extent because they believe it is effective, not because they know that it is about to rain anyway. Trickster. Some try to overcome this by suggesting that the deviant, yet perceptive, rainmaker is tricking the wider community. This idea implies a naivety that is not supported by the facts. The earlier argument about culturally practiced perceptiveness is relevant again. In addition, there are many Dreaming stories involving a trickster, who in one way or another fools another individual, or the entire community. This invites the proposition that people are quite aware of the possibility of being conned and would be capable to keep an eye out for it. Chance. Mainly amateur reporters use another argument, even less satisfying than perception. Comfortable in their “scientific” knowledge that one could never make rain by chanting and dancing, they simply dismiss any successful occasion they may observe as a stroke of luck. Exception. The following view of the anthropologist Long is still an exception: In spite of many observations of such phenomena by anti-psi anthropologists, even they cannot find failures in rainmaking to equal the successes. Hence, contrary to what is known about atmospheric causation, one is inclined to accept that rainmaking (and stopping) is successfully practiced and has a very high survival value. (Long, 1977, p.384) The Social context of rainmaking Terminology. Anthropology classifies rain making together with other ritual activities as imitative or sympathetic magic (Frazer, 1996; Tonkinson, 1972, p.67). These terms refer to ritual actions that in some form imitate or incorporate the characteristics of that which they seek to influence. Outcome. Sympathetic magic can be divided into two different forms according to the desired outcome. Increase or maintenance ceremonies are usually social activities concerning the well-being and economic obligations of the wider group. Witchcraft or sorcery is usually an anti-social activity aiming at the well being of one particular person to the detriment of other people. Responsibility. In Aboriginal Australia, different groups of intraphysical consciousnesses within a given society are responsible for different species in the natural environment. Usually this responsibility will arise from the totem of the intraphysical consciousness. Totems. In many societies, a totem is obtained by birth or conception at a particular place, or by inheritance. Totems are usually a species of flora or fauna; more importantly they relate to one or more Dreaming ancestors, i.e. extraphysical consciousness. Inter-dependence. Traditionally, individuals and their totem were inter-dependent: humans might have physical or psychological features relating to those of their totem (paragenetics) and special obligations for their totem. Increase ceremonies. For example, humans of the kangaroo totem will be charged with ensuring a sufficient supply of kangaroos by regularly attending to the kangaroo increase ceremonies. In most societies, people with the primary responsibility for rainmaking would have rain as their totem, or one of the ancestral beings associated with making rain, often a serpent referred to in English as the “rainbow serpent” (Poirier, 1997; Tonkinson, 1972). Censure. Should a certain species be scarce one year, others may censure those of that totem for failing in their duties. Rainmakers may be censured for the absence of rain, but also if there is a surplus leading to destructive floods (Trezise, 1985). Witchcraft. Detailed ethnographic accounts of Aboriginal Australia are replete with references to sorcery, usually malign and with the aim of killing or mentally disturbing another intraphysical consciousness. Most of these practices are secretive and involve one individual or a group focusing intensely negative energies at another individual, who is “sung” or “pointed” (e.g. Elkin, 1994, p.40; Howitt, 1996, pp.359-378; Peile, 1997, pp.137-139; Warner, 1937, pp.194-210). Revenge. People could make or withhold rain, and produce storms or lightening in revenge to kill or harm others (e.g. Hercus & Koch, 1996; Tonkinson, 1972, pp.115-116). While it could be used for negative, individualistic purposes, more commonly it was a beneficial activity, only done at socially recognised times and by the appropriate people. Networks. Even where rainmaking ceremonies were not communal events, but confined to a few specialised rainmakers, these did not operate in a social vacuum. They were part of regional networks and their abilities and role were recognised far beyond their immediate group. Rainmaking was not a frivolous activity. Influencing the weather Psychokinesis. Parapsychologists have satisfied themselves that human consciousness can produce small effects on intraphysical events (psychokinesis). Most experiments have focused on the ability of the human consciousness to influence random number generators or dice. Reviewing the available data on these experiments, Radin (1997, p.144) concludes that there is evidence that consciousness can act upon physical systems through the force of will. Systems. Weather is a substantially larger system than a number generator or dice. It is influenced by a complex interplay of evaporation, forests, geography (geo-energies), lunar energies, pollution, solar energies, volcanic activity, winds and many other factors. Extraphysical consciousness. Crucial to this discussion is the hypothesis that, as well as many physical variables, extraphysical consciousnesses play a role in regulating the weather on this planet. Climate. The weather is not the same as the climate. The climate of an area is determined by the composite of its weather over a prolonged period. A day’s weather is a building block for the macro-system of climate. The climate is a much greater system to change than the weather. Wishing. Radin cites a study by Nelson that compared the weather at Princeton University on graduation days with those of six surrounding towns. The theory was that the thousands of people coming to Princeton that day would be wishing for good weather. The study “revealed that on average, over thirty years, there was indeed less rain around graduation days than a few days before and after graduation, with odds of nearly twenty to one against chance. An identical analysis for the average rainfall in six surrounding towns showed no such effect.” (Radin, 1997, p.172; cf. Nelson, 1997) Sunday. A less detailed study, based on the same assumption, in this case that people would wish for good weather on Sundays, found a similar suggestion. “According to newspaper records, there were 211 days when the sun did not appear by afternoon press-time at St Petersburg, Florida, from 1910 through 1957. Only eleven of these days were Sundays.” (Cox, 1962, pp.172-173). Field-consciousness. Radin uses the term field-consciousness to describe the effect of larger numbers of intraphysical consciousnesses focusing on the same event. Conscientiology would speak of a group-holothosene. The field-consciousness Radin describes is often produced unconsciously, as in the many individuals wishing for good weather. Discipline. Aboriginal rainmakers are mentally and energetically well-trained. Meditative and projective techniques were part of their culture as were other forms of mental discipline. Intention. It is the hypothesis of this author that consciously focused intent of only a few such individuals is more likely to influence the weather than the idle wishes of a larger population desiring a sunny Sunday. The structural elements of the ceremonies Essentials. In spite of the great variety of rainmaking ceremonies across Australia (McCarthy, 1953), there are recurring essential elements. They may not all occur in every ceremony, but they stand out in the literature surveyed. Those elements are now analysed from a bioenergetic, holosomatic and multidimensional perspective. Composite. While presented here in isolation for the sake of analysis, in the ceremonies the elements come together as a composite whole, creating an atmosphere of purposeful, highly charged thosenes, sometimes over several days of intent ceremonial activity. Arm Movements to direct clouds Example. “Then a bundle of emu-feathers tied together ... is thrust out towards a cloud and drawn (or waved) slowly back towards the operator. This is repeated many times (when another cloud is selected for a similar operation ...) to bring all the clouds together, then “big fella rain tumble down”. (Reid, 1930; cf. also Cherbury, 1932; Mathew & Anau, 1991) Auric coupling. The intraphysical consciousness (the rainmaker) is consciously promoting an auric coupling [i.e. a connection] between the hydro-energies of the clouds and his own bioenergies and using his energies as a lever, to will the movement of the clouds. Control. Consciousness can control energies and as we develop our holochakra and our ability to perceive and focus on energies beyond the soma, we can consciously extend our sphere of influence; for better or for worse. Extraphysical assistance and projections Projective account. The following is the account of a projection to produce rain, recorded by the anthropologist Ronald Berndt among Wiradjuri people in western New South Wales. It is interesting to note the distinctly cultural elements of the projective experience as well as the universal elements such as the silver cord (maulwar cord), the importance of controlling emotions and the temporal incongruence: As informants stressed, it took a very clever doctor to go unharmed through the dangers which accompanied a journey to the world behind the sky, where the water-bags were kept. When it was necessary, and only then, a discussion would be held between the tribal elders, headmen and doctors as to the advisability of obtaining rain. A doctor would be chosen, and a particular time named when he would undertake his skyward journey. On the auspicious night, he would “sing” all the inmates of the camp, so that they would sleep soundly, and not hear any noise that he might make or cause. He would then sit away from the camp and “sing” the clouds down so that they were about fifty to sixty feet from the ground; so near were they that “the noise of birds and ducks could be heard.” He would then sing out his ‘maulwa(r) cord and send it vertically up towards the clouds; it “would be just like putting a pole up”. He would lie on his back, his head upon his chest, with legs held up above the ground; in this way, watching the cord he would “sing” himself up. As the cord moved upwards past the clouds, it lifted the doctor who was suspended “like a spider.” Coming to Wantangga’ngura he let his cord gradually return to his body and standing upright looked around. He could see the darkness of the night sky, and all the stars, which were the various Ancestral Beings who had in the past climbed up here; being so close to them he could see their human form, whereas from the earth they appeared merely as points of light of varying brilliance. But he did not look long, since he was still outside the place in which the water-bags were kept; this place was called ‘Pali:ma, and was in the Wantangga’ngura country. To pass into Palima, the doctor had to go through a fissure, through which the Ancestral Beings had passed when they left the earth. This fissure or cleft was termed ‘mupara:m (...), and its two walls were continually moving around; this was demonstrated by the informant who used the open palms of both hands, placed them together, and rubbed them in a circular manner. The revolving of the ‘mupara:m left a small aperture which was revealed at intervals; it was through this latter that the doctor had to pass. ... Watching the revolving ‘mupara:m till an aperture appeared, the doctor entered and found himself in Palima, a country much the same as the earth, having also a sky above it. As he walked to and fro, looking around for the hut in which were stored the water-bags that had been sent up by the Eaglehawk, two Ancestral Men called Ngintu-Ngintu and Kunapapa ran up. Both carried clubs. The former began to call out a volley of questions, endeavouring to discover why the doctor had made this journey and entered the ‘mupara:m; but the “clever man” would not answer his questions, since otherwise he would be thrust out of Palima. Before Ngintu-Ngintu and Kunapapa were near, the doctor stopped walking – they must not see him doing this for if they did they would kill him at once. Coming up close to the “clever man”, who now sat down, they began to corroboree. They would dance and sing in the most humorous way, their intention being to make their onlooker smile, laugh or talk; should he do any of these things they would kill him. They danced with their legs well apart; their very long penes waved from side to side, and with the motion of the dance became erect and moved up and down; the doctor did not even twitch his lips. Then with their hands they made as if to poke out his eyes, but the other did not flicker an eyelid. They stared at him, coming close up and looking into his eyes; but still he did not blink or smile. After a while, Ngintu-Ngintu and Kunapapa became tired of receiving no response on the part of the doctor and sat down to one side. Then some women came up and began to corroboree in front of the doctor. They danced in an erotic manner, shuffling along with legs apart and knees bent; as they came close up to the “clever man”, they assumed an inviting posture and acted in other erotic ways. The doctor, however, still remained immobile; if he had been affected by, or if he had made any movement towards the women, he would have been killed. At last the women joined Ngintu-Ngintu and his companion and began to talk amongst themselves, each asking the other what could be done with the doctor. While they were thus engaged the latter “sang” away all of them except Ngintu-Ngintu, who was too powerful to be disposed of in this manner. Then taking out of his small skin bag a ‘nginbaran (emu anus-feathers tied in a bunch) he threw it into the distance and began to sing. The singing created from the bunch of feathers an emu; as the bird became visible the doctor called out to Ngintu-Ngintu ... : “There goes an emu”. Ngintu-Ngintu who was a keen hunter, gathered his spears together and rushed in the direction of his hut, in order to get his dog. While he got his dog, which went after the emu, the doctor sprang up and darted across to the hut in which the water bags were stored. Once there he speared one of the water-bags; as the water spurted out the doctor ran over to the ‘mupara:m in order to escape. However, Ngintu-Ngintu and his dog, who had found out that the emu created by the doctor was not of material substance, saw him running, and saw the water from the bag flowing to the fissure. The dog rushed over to the doctor, and snapped at him urged on by Ngintu-Ngintu. But the clever man reached the mupara:m unharmed; he escaped through it, and just as the dog put his head through it he “sang” the mupara:m closed (i.e. he stopped it revolving). When “he got well out of sight of the dog he sang the mupara:m loose (i.e. open)”. As it opened the water gushed out; because it had been kept in the skin bag since ‘ngerka:nbu times, the water was “stinking” and bad. When the doctor got the water “on this side” (i.e. out of Palima), he “sang” all the clouds up; into these poured the water, to be sieved and purified into clear water, to come down as rain either at once or a little later on. He then “sang” out his cord, and “climbed” down towards the same place from which he had gone up. The next morning he would say to the others: “See it is raining now”, or “It will rain soon”. His actual journey was said to have taken no more than a few seconds (Berndt, 1947, pp.361-363). Implicit. Aboriginal people often imply the importance of extraphysical consciousnesses in rain making by statements that claim that the success or failure of a ceremony depends on the co- operation of certain Dreaming ancestors. Extraphysical consciousness. Although it is not possible here to illustrate the role of extraphysical consciousnesses in weather phenomena, I do accept Vieira’s theory that they play some role in all natural phenomena (Vieira, personal comment during the course “Sensibilização Energetica”, Foz de Iguaçu, 1997). Evocation Imitation. Ceremonial participants will imitate the calls and actions of creatures related to water, such as ducks, fish, frogs, pelicans, swans and others. Such acts serve to focus the mind of the participants and evoke the atmosphere during which such creatures are usually encountered. Ceremonies. Feathers are a key ingredient to many ceremonies, being one of the few traditional items for creating “costumes” or for general adornment. Using the feathers of water birds may serve to establish an energetic link with those creatures, and by implication their moist habitat. Human Blood Sacrifice. Many agricultural societies sacrifice the lives (soma) of animal and even human intraphysical consciousnesses in their rituals, in the belief that this will please the Gods and make them grant a desired physical outcome, for example rainfall. It is possible that there were extraphysical consciousnesses associated with those rituals who would indeed see that the wishes of the intraphysical sacrificers were fulfilled. Pathology. The actions of the intraphysical and extraphysical consciousnesses in such cases are pathological to the extreme. Sacrifice of that kind is a social institution based on energetic vampirism of the life energy of the intraphysical victims. While it may bring immediate results during one intraphysical life, it leads to multi-existential stigmas and groupkarmic interprison. Bloodletting. Human blood is used in many Aboriginal ceremonies, but neither human nor sub-human animal is killed. The individual sacrifices from him or herself. Usually men will tie their upper arms tightly with a ligature and open a vein in their lower arm. The blood is collected in vessels or applied directly to the bodies of other ceremonial participants. It is drunk or sprinkled on objects and is used as a glue to attach feathers, wood shavings or other forms of decoration. Power. From the Aboriginal perspective blood has various powers. Its external application or consumption is thought to energise. It is also considered to feed the Dreaming ancestors. From a bioenergetic perspective, a person’s blood is a very strong carrier of their holothosenic imprint. From a multidimensional perspective, blood can be a food for tropospheric extraphysical consciousnesses and its density may facilitate inter-dimensional psychokinetic (PK) phenomena. “Rain stones” and pearl shells Shells. Throughout the Australian Western Desert pearl shells traded from the north-west of the country are used in rain ceremonies (Berndt & Berndt, 1944; Mountford, 1962, p.138). A part of the shell is ground into liquid, blood or spittle, which is then either ingested or spat out in various directions. Ocean. The connection between the shell and water, in this case the ocean, is obvious. Rain Stones. In other parts of the country, clear crystals are used in a similar way. A certain area along the Birdsville track in northeastern South Australia used to be called “rain country” because it is prolifically covered in gypsum, the “rain-stone”. Moisture. One researcher notes that his Aboriginal informants “observed the water-absorber mineral gypsum, and, on perceiving moisture induced changes or deliberately moistening the gypsum to promote such changes, crushed the mineral to free the water spirit.” (Kimber, 1997, p.8) Amplification. Crystals form a part of many “magical” practices among indigenous and non- indigenous people, possibly for their capacity to amplify the bioenergies of the intraphysical consciousness manipulating them. Red ochre Energise. Ochre is an essential ingredient to almost every ritual practice among Aboriginal people. It is applied to the body and ceremonial objects and is thought to energise. Often, red ochre is considered the metamorphosed blood of Dreaming ancestors. Grounding. From the bioenergetic perspective, the geoenergies of the ochre would arguably ground the individual applying it. Songs and Chants Words. The power of words is used in most indigenous societies. In Aboriginal Australia there are songs for many ends. People speak of having been “sung” to describe the acts of sorcerers who sing harmful songs to hurt their victim. Healing also occurs through song. There are songs for every “sacred site” and through singing them the places are energised and “come to life”. There are songs for increase ceremonies, to attract a desired lover and to influence the behaviour of humans and other animals. There are songs to make rain and songs to cause drought. (e.g. Hume, 2002, p.94; Martin 1988, p.26, Strehlow, 1971) Rules. Because of their power, songs are transmitted according to strict social rules. Composers. Ceremonial songs are never considered the product of human composition. They are thought to be ancient, from the Dreaming and composed by the Dreaming ancestors. Songs are either handed down across intraphysical generations or are the result of revelations during projections in which intraphysical consciousnesses are given the songs by the extraphysical consciousnesses “from the Dreaming” (Poirier, 1996; Strehlow, 1971, p.260). Repetition. Arguably, their repeated use over millennia has increased the bioenergetic charge of the words and actions in the same way as that of objects is increased through repeated use (psychometry). Effects. That words and songs should have physical effects of the magnitude contemplated by Aboriginal traditions is not supported by conventional science. From a multidimensional perspective the source of their power could lie in:

Objects Tjurunga. Engraved stones and pieces of wood were used as ceremonial objects throughout Aboriginal Australia. Among the Arrernte speaking people of central Australia they are called tjurunga, and anthropologists often use that term generically. Individual. Different ceremonies and different places in the landscape have their own individual objects, only brought from hiding at the appropriate time. Like the songs, these objects are considered the product, or even the embodiment, of the Dreaming ancestors (extraphysical consciousness). Attention. During ceremonies, these objects are subject to close attention; they are handed from person to person with each individual consciously exchanging energies with the object. People will meditate on the objects and sing the appropriate ceremonial songs while contemplating them. Reinforce. Like songs, the objects seem to function as a connector to extraphysical dimensions, and a way of tapping into an old and powerful source of consciential energies that has been reinforced over generations. These energies are channelled towards specific purposes according to the designated function of the ceremony with which the tjurunga is associated. Water Water. Most ceremonies involve sprinkling, splashing or diving into water. In some cases, participants spit. The sympathetic element is obvious; participants are seeking to replicate rainfall to attract or induce the real thing. Summary. To summarise, a rainmaking ceremony is composed of a set of energetic, physical and mental actions designed to fully focus the consciential energies of the participating intra- and extraphysical consciousnesses. In some cases, the rainmakers use the more direct method of conscious projections to influence the weather from the extraphysical dimensions. Serene. The Homo Sapiens Serenisimus does not require a ceremony to influence the weather. He or she does it directly through his or her holosoma. (Vieira, 1994). Conclusion Deficiency. This study is deficient in that it is only based on theory, not practice. I have not personally attempted to make rain while writing this article. I have, however, witnessed an Aboriginal man sing a rain song and this lead to unexpected torrential rainfalls less than 12 hours afterwards, and I know of numerous similar stories from other fieldworkers. Experiment. It is tempting to suggest an experiment whereby groups of people gather and, after going through the standard mobilization of energies, spend 10 or 20 minutes focussing their group-energies on the desire to produce rain. Such experiments may be inappropriate, however, due to the magnitude of the system being manipulated. Disaster. Physical rainmaking experiments (cloud seeding) in western England, for example, are linked to disastrous floods that killed 35 people in 1952 (BBC News, 13.01.2003). Once rain begins to fall, it is not easily stopped. Timing. This may be why Aboriginal people were cautious in making rain and preferred to do it during the appropriate time, i.e. when rain was naturally expected. Rain would only be made on other occasions after careful deliberation. Superiority. It should be pointed out that this article does not assert that traditional Aboriginal society was somehow superior to our own, simply because of its active working with multidimensionality. Pathology. Just as the pathologies in our society are highlighted by the headlines dominating our media, so the pathologies of Aboriginal society are highlighted through the recurrent theme of malign sorcery and fear based social control. Cosmoethics. If the term “superiority” is meaningful at all, it is so only on the individual level, in reference to the level of cosmoethics manifested by the consciousness, whether intra- or extraphysical. Logic. This article seeks to logically explain something that I have not seen explained elsewhere. As I am not a rainmaker I cannot pretend to know all the answers or understand all the details. So please dear reader, let me know of any omissions, errors or lapses of logic, so that I can improve my argument in the future. References ANONYMOUS; How to Make Rain; newspaper clipping found in AA3, South Australian Museum Archives; not dated. ANONYMOUS; Rain-making by the Aborigines: Remarkable savage ceremony at Poolamacca in Newsletter of the Royal Australian Historical Society; Oct.-Nov. 1978. BERNDT, Ronald & BERNDT, Catherine; A Preliminary Report of Field Work in the Ooldea Region, Western South Australia in Oceania 15(2); 1944; pp.124-158. BERNDT, Ronald & BERNDT, Catherine; The World of the First Australians; Ure Smith, Sydney; 1964. BERNDT, Ronald; Wuradjeri magic and “clever men” in Oceania 17(4); 1947; pp.327-365. CHERBURY, Chas. P.; Rain-making in Western New South Wales in Mankind 1(6); 1932; p.138 COX, William E.; Can wishing affect weather; in I.J. Good (ed.) The scientist speculates; Basic Books, New York; 1962. DE MARTINO, Ernesto; Il mondo magico: Prolegomeni a une storia del magismo; Bollati Boringhieri, Torino; 1997 (1973). DUERR, Hans Peter; Traumzeit: Über die Grenze zwischen Wildnis und Zivilisation; Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main; 1985. ELKIN, Adolphus Peter; Aboriginal Men of High Degree; Queensland University Press, St. Lucia; 1994 (1945) FRAZER, James George (Sir); The Illustrated Golden Bough: a study in magic and religion; abridged by Robert K.G. Temple; Simon & Schuster Editions, New York; 1996 GODDARD, R.H.; An Aboriginal Rain-Maker in Mankind 1(3); 1932; p.84. HERCUS, Luise & KOCH, Grace; ‘A native died sudden at Lake Alallina’ in Aboriginal History Vol.20; 1996; pp.133-149. HERCUS, Luise; Tales of Ngadu-Dagali (Rib-Bone Billy) in Aboriginal History 1(1); 1977; pp.53- 76. HORNE, G & AISTON, G.; Savage Life in Central Australia; Macmillan and Co., London; 1924. HOWITT, A.W.; Native Tribes of South-East Australia; AIATSIS, Canberra; 1996. HUME, Lynne; Ancestral Power: The Dreaming, Consciousness and Aboriginal Australians; Melbourne University Press, Melbourne; 2002 KIMBER, Dick; Cry of the plover, song of the desert rain in Eric K. Webb (ed.) Windows on Meteorology; CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood; 1997; pp.7-13. LONG, Joseph K.; Extrasensory Ecology: A summary of evidence in Joseph K. Long (ed.) Extrasensory Ecology: Parapsychology and Anthropology; The Scarecrow Press, Metuchen, N.J & London; 1977; pp.371-396. MARTIN, Sarah; Eyre Peninsula and West Coast – Aboriginal Fish Trap Survey; South Australian Department of Environment and Planning, Adelaide; 1988. MATHEW, Aggie Pinu & ANAU, Jerry; The Rainstones inBoigu: Our history and culture; Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra; 1991. MCCARTHY, Frederick; Aboriginal Rain-Makers in Weather 8; 1953; pp.72-77. MOUNTFORD; C.P.; Brown Men and Red Sand; Angus and Robertson, Sydney; 1962 (1950). NELSON, Roger D.; Wishing for good weather: a natural experiment in group consciousness in Journal of Scientific Exploration 11(1); 1997; pp.47-58. PEILE, Anthony Rex; Body and Soul: An Aboriginal View; Hesperian Press, Carlisle; 1997. POIRIER, Sylvie; Les jardins du nomade; Lit Verlag, Münster; 1996. RADIN, Dean; The conscious universe: The scientific truth of psychic phenomena; Harper Edge, San Francisco; 1997. REID, C.W.; A Note on Aboriginal “Rainmaking Ceremonies” in Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society (SA) 30; 1930; pp.80-82. ROSE, Debbie; When the rainbow walks in Eric K. Webb (ed.) Windows on Meteorology; CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood; 1997. STREHLOW, T.G.H.; Songs of Central Australia; Angus and Robertson, Sydney; 1971. TONKINSON, Robert; Nga:wajil: A Western Desert Aboriginal Rainmaking Ritual; PhD Thesis University of British Columbia; 1972. TREZISE, Percy; Rain-making sites in the Mosman River Gorge; unpublished manuscript; 1985. WARNER, W. Lloyd; A Black Civilization: A social study of an Australian tribe; Harper & Brothers Publishers; 1937. WHITE, Isobel; Rain ceremony at Yalata in Canberra Anthropology 2(2); 1979; pp.94-103. VIEIRA, Waldo; 700 Experimentos da Conscientiologia; Instituto Internacional de Projeciologia e Conscienciologia, Rio de Janeiro; 1994.

0 Comments

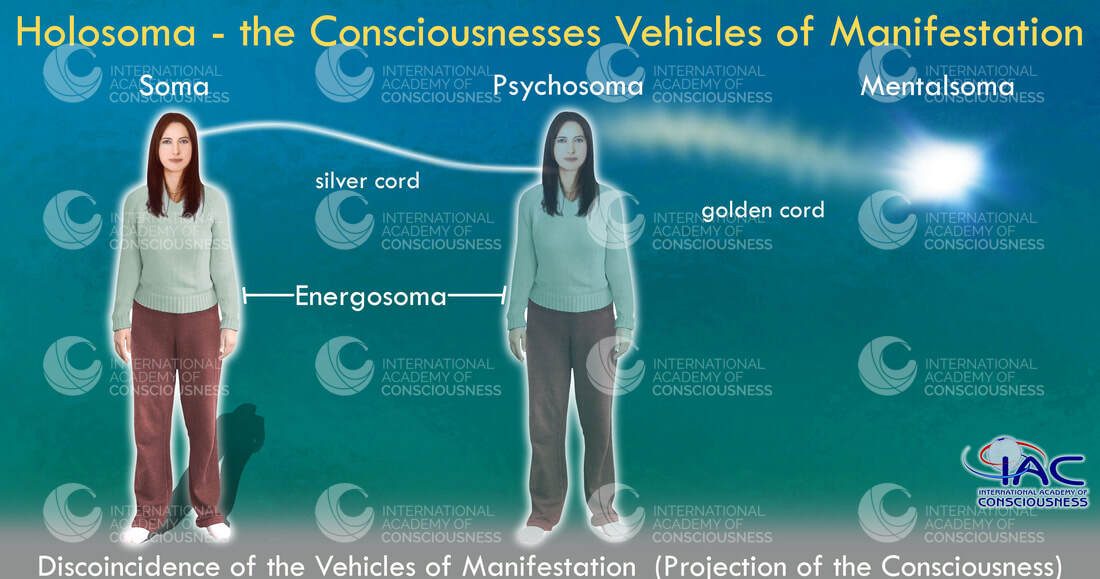

8/9/2019 You are a consciousness having a physical experience - a personal out-of-body accountRead NowThe following account is of an experience I had more than 20 years ago, but its profound impact on my sense of self has resonated throughout my life since. You may have heard it said that we are not really human beings having spiritual experiences, that we are not really “going out of the body” in an OBE, but really that we are spiritual beings having a human experience. From that perspective this human life is one long "in-body-experience" of a consciousness whose real home is beyond the physical dimension. The projection of consciousness I describe below made this idea very tangible for me. I truly came to experience my real self as something much vaster and expansive than the personality of my current life. At the same time I came away with a strong sense of the importance of not alienating myself from my current physical life by focusing too much on what I consider my real multidimensional identity. Even if I do not fully understand the purpose of my current life in the scheme of the vastness of existence that I glimpsed, I was given the understanding that the best thing I could do for my own evolution was to live a strongly integrated physical life. After all, that is why we are here. Embodying our consciousness in every aspect of our physical life is a task that can prove to be much more challenging than the pursuit of transcendent states. It is certainly a task that has challenged me ever since, as there always seem to be more areas of life to integrate and it is precisely these challenges that seem to make our lives such amazing opportunities for learning and growth. Background To help with understanding the below account, I briefly give an outline of the way I have come to conceptualise our various out-of-body states. The picture below shows the different bodies we, as consciousnesses, use. Of course there is the physical body, which is our densest “vehicle of manifestation”, and consciousness uses it to manifest itself in this physical dimension. When we fall asleep, we normally separate ourselves from the physical body in a more subtle vehicle, designed for more subtle dimensions. This subtle body is known as the astral body, the spirit body, or in conscientiology as the psychosoma or emotional body. It looks pretty much like a replica of the physical body, although this appears to be more a result of our psychological conditioning rather than a fundamental quality of the psychosoma. In fact, the psychosoma is highly suggestible to our thoughts and emotions, and we are in theory able to completely change its appearance. But for the most part we go with what we are familiar with, shaping it from our subconscious according to our self-image. Beyond the psychoma is the mentalsoma, or mental body. This body is very subtle, and basically formless. It still seems to consist of some kind of energy, but it does not share many other attributes that we normally associate with a “body”. As far as we know, consciousness is beyond the mentalsoma again. So the mentalsoma is another vehicle just like the physical body and the psychosoma. But because the mentalsoma is that much more subtle and that much closer to consciousness it gives us uniquely transcendental experiences. Projections in the mentalsoma are considerably rarer than in the psychosoma, and often accompanied by profound experiences described by terms such as cosmic consciousness, oneness, god experience and so on. This is the kind of experience I share here. What made this experience especially compelling for me, were the very tangible energetic phenomena that accompanied it and truly set it apart from other projections I have had. The projective experience itself was profound, but also extremely subtle. So the energetic phenomena provided personal corroboration that something out of the ordinary had truly happened. The following text is as I wrote it down at the time with a few clarifying comments in brackets. Pre-projective period

I was taking the second stage of a course in projective techniques at the IIPC’s office in Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro. The course took place over four consecutive days from May 11-14, 1998. Ever since the course began I had noticed a difference in my nocturnal perceptions, with more lucid projective experiences. During the course itself, although I had had a sense of having been projected, so far I had not had any experiences I could recall. The last lesson was the technique of projecting with the mentalsoma. There had been three or four students in each of the previous classes but today I was alone with the instructor. (This seemed significant to me, because it felt I was getting special attention, not just from the physical instructor, but more importantly from the extraphysical team of helpers supporting the course) I did not have any expectations and felt calm although with many thoughts relating to my daily life running through my mind. These continued even during the energetic exercises preceding the technique (Basic Mobilization of Energies, which consists of various mental exercises to move our energy (Chi or Qui) throughout our energetic body) . During the absorption of energies, the final exercise before starting the technique itself, I felt a lot of activity in the two superior chakras (frontal and crown) which seemed to form one single chakra, situated more or less half-way between the two. The inside of my head appeared to heat up from the inside out, starting from the pineal gland until the heat focussed itself on this midway point between the chakras. So far I had been sitting and now as I lay down this part of my body remained active. After being talked through the psycho-physiological relaxation (a deep muscle relaxation technique), I put all my attention into this energetic process, knowing (intuitively) that it was the “entrance” to the mentalsoma. Projective period There was no sense of “take off” whatsoever. It merely felt as if the body disappeared and instead, I found myself in a vast space, or rather it was I who was vastly spacious, expanded. This occurred without any great sense of ecstasy or even the feeling that this experience was in any way special. It simply felt like a change of environment or better of perception. I felt as if I was looking at my intraphysical life from the outside. From here I saw that all the hazards of life, and all those events which we might call “intrusions” are nothing other than energetic phenomena. This realization made me feel very calm. I wondered how they managed to appear so “real”. I understood that I was not the person who was having the projection of the mentalsoma, but rather a mentalsoma who was having the experience of being an intraphysical being. In an inversion of the usual perception which sees the ‘I’ going from the intraphysical to engage in extraphysical experiences I saw that in relation to the infinity of the mentalsoma any experiences of the personality with which I was currently identifying myself were merely ephemeral phenomena. I attempted to understand how the intraphysical experiences of the intraphysical consciousness related to this timeless state of the mentalsoma, i.e. what is the meaning of life?, without succeeding, but also not really caring too much about the answer. Post-projective period I had no awareness of any interiorization and no sense of the time that might have passed. When my perception returned to the soma it was rigid, the hands were cold, and balls of hot energy were pulsating at the base of my spine as well as at the top of the head. Now the crown chakra was distinctly active. I spent another ten minutes or so lying there without moving until the instructor gave the command to return to intraphysicality (as the projection time was scheduled for 60 minutes, the whole experience would have lasted about 45 minutes). My mouth was dry and my body felt at the same time rigid and subtle. The experience had energetic impacts which lasted at least for the subsequent two weeks during which I felt my holochakra expanded and my mind much calmer than usual. It was easy to reestablish an energetic connection with the recently experienced projection and this caused an increase of my intraphysical vibrations. Gradually this faded. Observations The experience gave me some insights into a problem I had pondered for a while. Why don’t we manage to live more from the perspective of the time-less mentalsoma during our day-to-day life? One possible explanation might be the great difference between its reality and our intraphysical needs. The perception of the mentalsoma, when pure or naked, without the interference of denser energies, is so far removed from the needs of our day to day that bringing it into our life would have to be learnt slowly. Put differently, the intraphysical consciousness must be trained to know its own reality without alienating itself from itself, i.e. causing mental imbalances. When healthily balanced however, experiences of the mentalsoma can have profoundly curative and life enhancing capacities as they allow the intraphysical consciousness to act in knowledge of its actual extraphysical origin, thus providing a source of inner freedom and happiness. (I have previously published this account on the IAC blog as well as in my book. I know when I first wrote it I felt it's revelatory impact spoke for itself. Reading it now, it actually seems very low key and probably a bit obscure if you have not had a similar experience. But if you have I'd love for you to share in the comments how it came about and how it impacted your life, and of course if you have any questions about it I'd also love those.) |

Details

AuthorKim McCaul is an anthropologist with a long term interest in understanding consciousness and personal transformation.

About this blogThis blog is about my interests in consciousness, energy, evolution and personal growth. My understanding of consciousness is strongly influenced by the discipline of conscientiology and I have a deep interest in exploring the relationship between culture and consciousness.

Have some inputI am often inspired by comments and questions from other people, so if there is something that interests you drop me a line and I will see if I can write something about the topic.

Support my workIf you enjoy something you read here consider supporting my work in this field by purchasing my book, which is available on any major online book store. It's a win-win as you will get a mind expanding read and I will feel the support and encouragement to write other mind expanding books. If you have read my book and enjoyed it please consider leaving a review of it on Amazon to help others find it. I am a great believer in creating community in the online space and sharing our passion for understanding consciousness is an excellent way of doing that.

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|